Function calls {

Introduction

We’re going to look at the most fundamental kind of JavaScript instruction, the function call. A function is a way to tell our program to do something more complicated by just using a name and some information.

Preparation

- Download the template project

- Unzip it

- Rename the folder to

function-calls - Move the folder into your repository

- Open the folder in VS Code

- Give the program a title in

index.html(maybe “Function calls”) - Commit and push the changes

setup() and draw()

In script.js we see two functions by default: setup() and draw(). These are function definitions and we will learn about how useful this is shortly. For now, we need to know that if we write code inside the curly brackets of these functions, that code will “run” (or “happen”, or “execute”) when our program runs.

Code we put in setup()’s curly brackets will happen once at the start of our program.

Code we put in draw()’s curly brackets will happen every frame our program is running.

Create a canvas

For our first function call we will create the canvas we need to be able to display cool stuff on. So let’s modify setup() to do this:

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 480);

}

That new line is a function call that tells our program to, you guessed it, create a canvas on our webpage. A “canvas” is a part of HTML that lets us draw things (instead of using text and images via HTML tags). createCanvas() is letting us create it from inside our program.

There’s more going on here than just the name here, though, so let’s break it down.

createCanvasis the name of the function we are calling. It’s a good name because it describes what the function does: it creates a canvas.- Then we have a set of parentheses with stuff inside them:

(...). These parentheses are what tells JavaScript to execute the function with this name (without them it wouldn’t run). - Some function calls have nothing inside the parentheses, like

setup(), but lots of them have extra information needed to run the function called arguments. - For

createCanvaswe have two arguments that tell the function what kind of canvas to create. Specifically, they tell it the size of the canvas to create.- The first argument of

640tells it the canvas should be640pixels wide - The second argument of 480 tells it the canvas should be

480pixels high - The two arguments are separated by a comma so that JavaScript can see that there are two in this case

- Other functions may have zero arguments, or one, or two, or many more

- The first argument of

- After we close the parentheses to say we’re done providing arguments and that this function call should be executed we have…

- … a semicolon:

;. This just means “this instruction is done!”- Note: JavaScript does not always need the semicolon to be there to work, but it is a very good idea to include them because other programming languages you may want to learn do require them. May as well.

Draw a background

If we ran our program right now it would look underwhelming because we’re not drawing anything on the canvas. Let’s fix that by adding a new function call, this time in draw():

function draw() {

background(255, 100, 100);

}

Hopefully, you can see this has the same structure as the createCanvas() function call we added just before:

background: We have the function namebackgroundwhich is a function that tells p5 to fill the entire canvas with a colour of your choice(...): We have the parentheses that go around the arguments and also tell JavaScript to execute this instruction255, 100, 100: We have the arguments themselves that tellbackgroundextra information on what to do;: We have the semicolon at the end to say “done!”

Obviously the function name is different, because it has a different job: filling the “background” of the canvas with a color.

But we also have a different set of arguments. This time there are three and they are different numbers from before. What do they mean?

In this case they are the red, green, and blue (RGB) values to use when filling the canvas with a colour. They determine the colour that background will use. Importantly, they are numbers between 0 and 255. 0 is none of that colour. 255 is all of that colour. So:

255: is for the red amount in the colour and it means “all the red!”100: the first100is for the green amount in the colour, “a bit less than half the green”100: the second100is for the blue about in the colour, “the same amount of blue”

What is the resulting colour? Let’s see!

- In VS Code click on the

Go Livebutton at the bottom right of your editor - This should open your default browser (which should be Chrome ideally) and display your program

- Thus you should see a the beautiful pink background you filled the canvas with

Because our background function call is in draw() it is actually being executed every frame, but since it always draws the same pink colour we don’t see anything change.

Positions on the canvas

In order to draw things at specific positions we need to know how to refer to those positions on the canvas with numbers. Because computers love numbers. In this case we’ll be talking about coordinates.

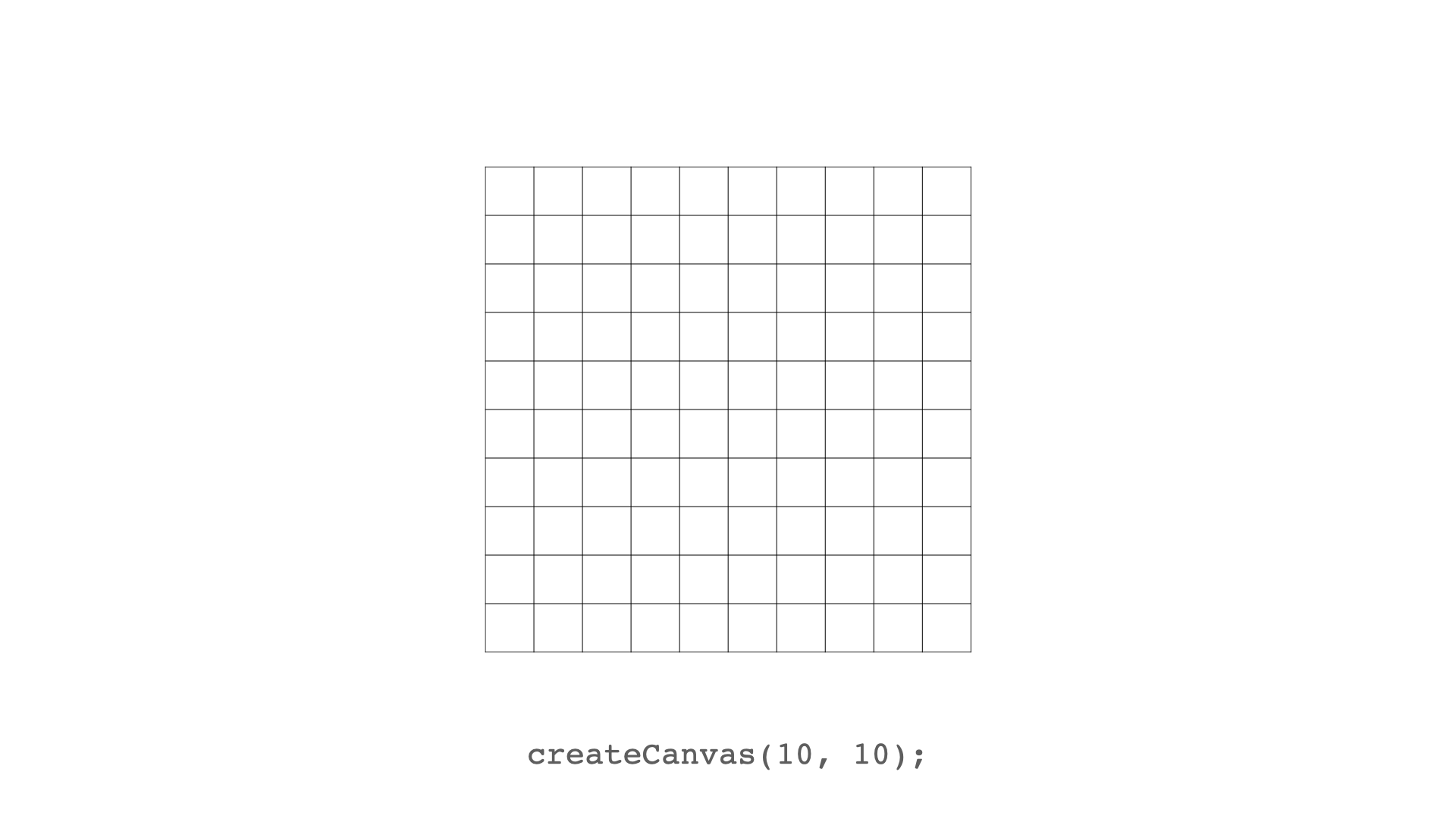

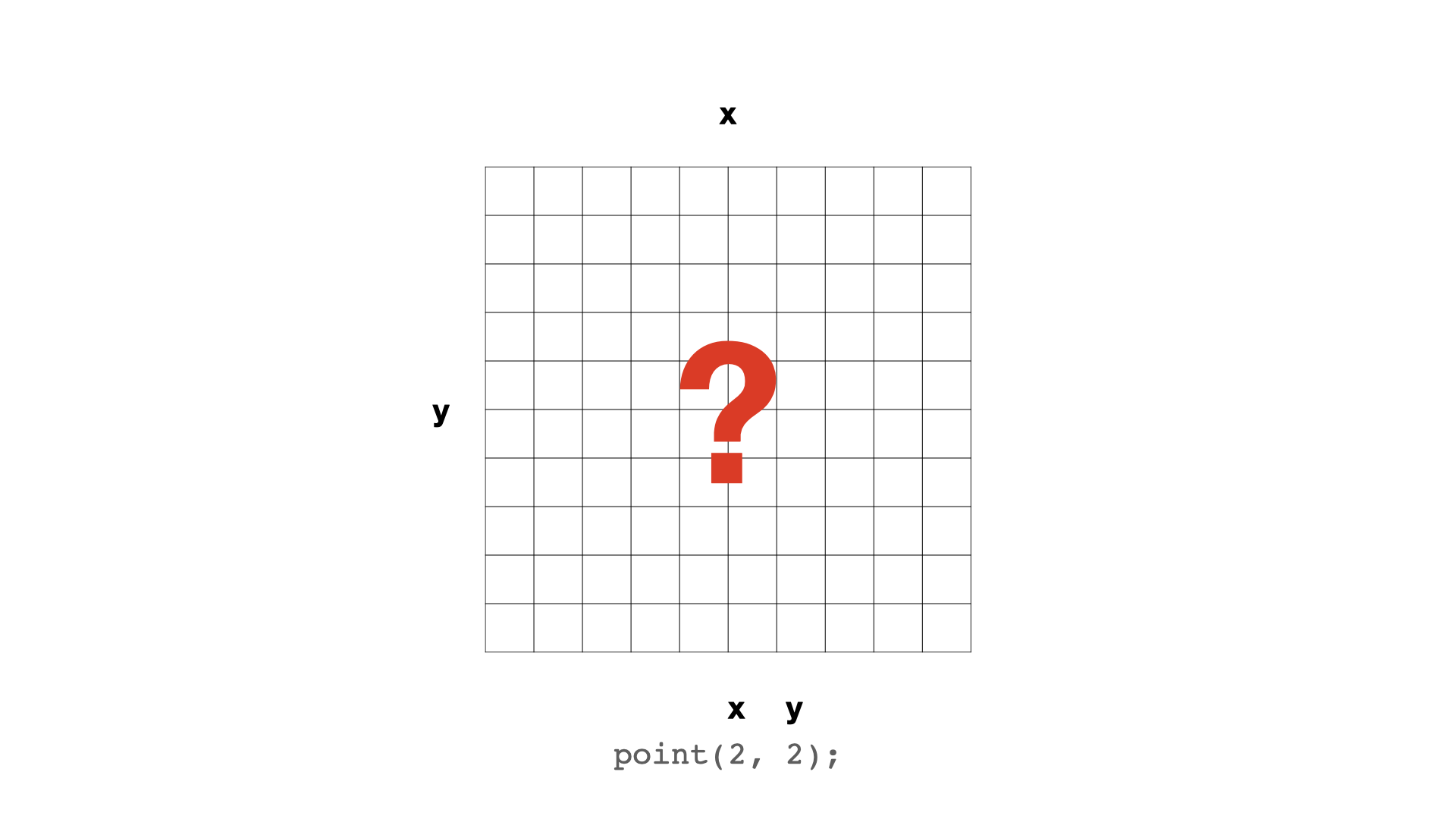

So, if we create a tiny 10x10 canvas, it looks like this.

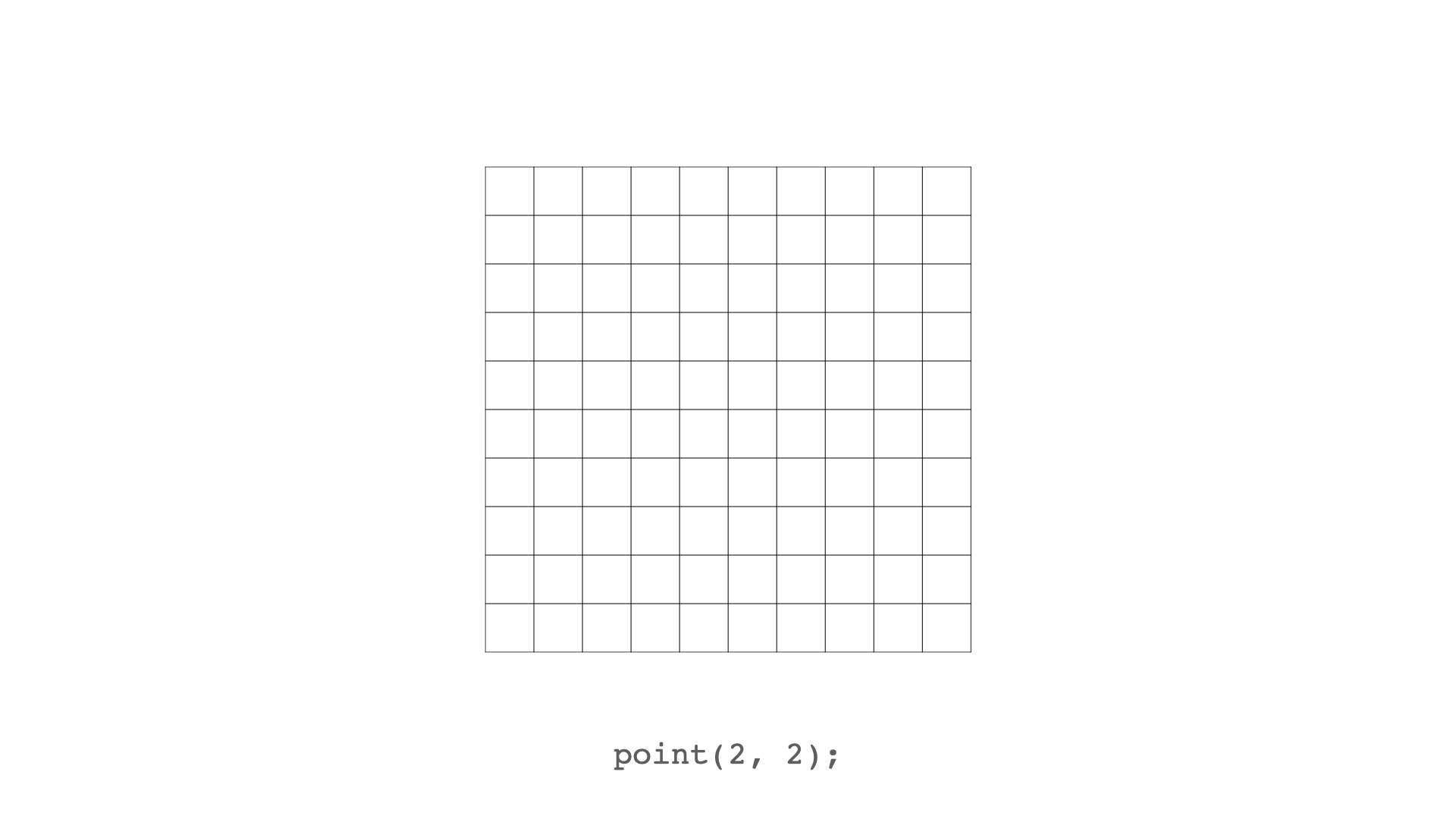

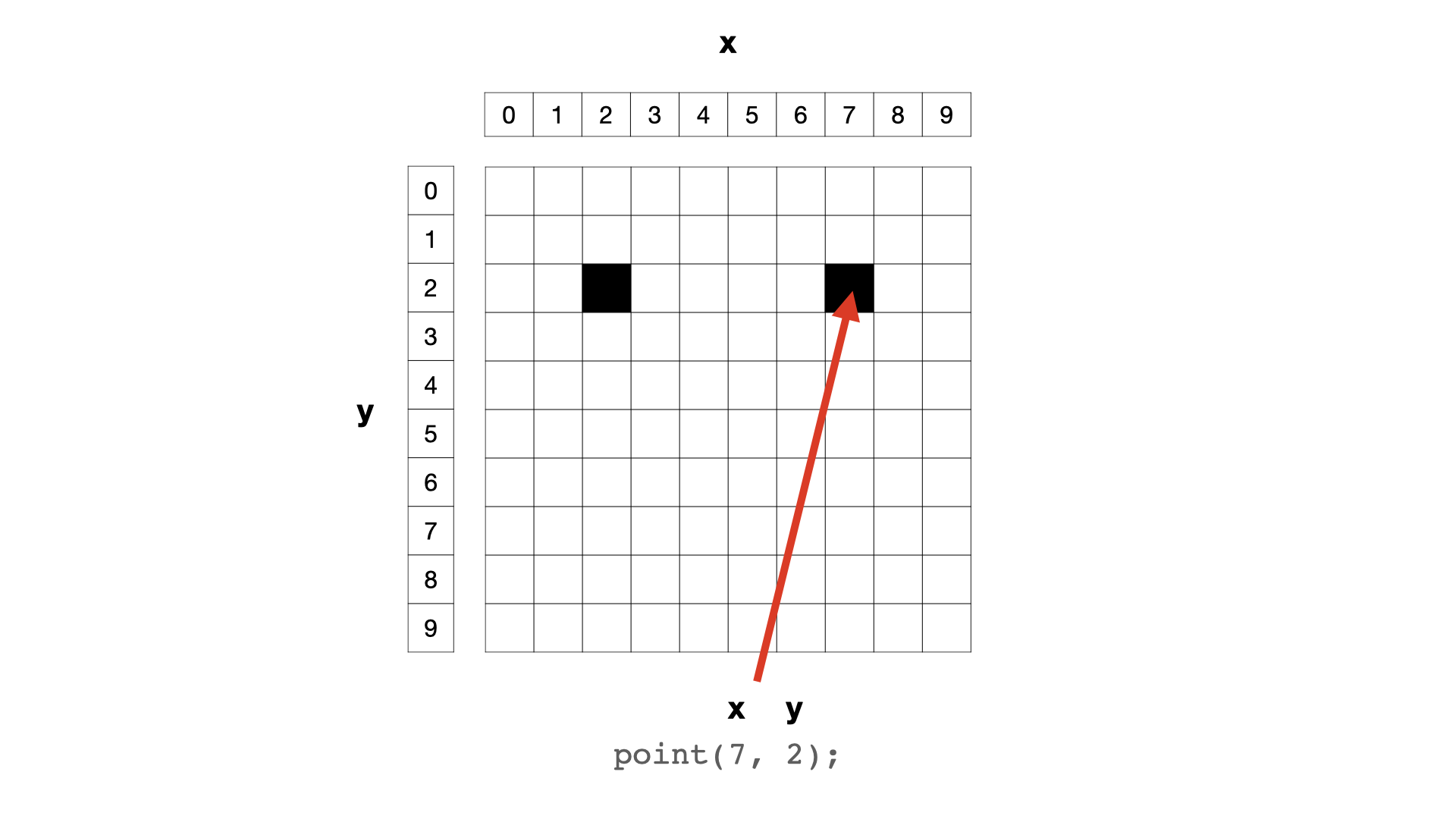

We can then draw a point (a single pixel) at the coordinates (2, 2)…

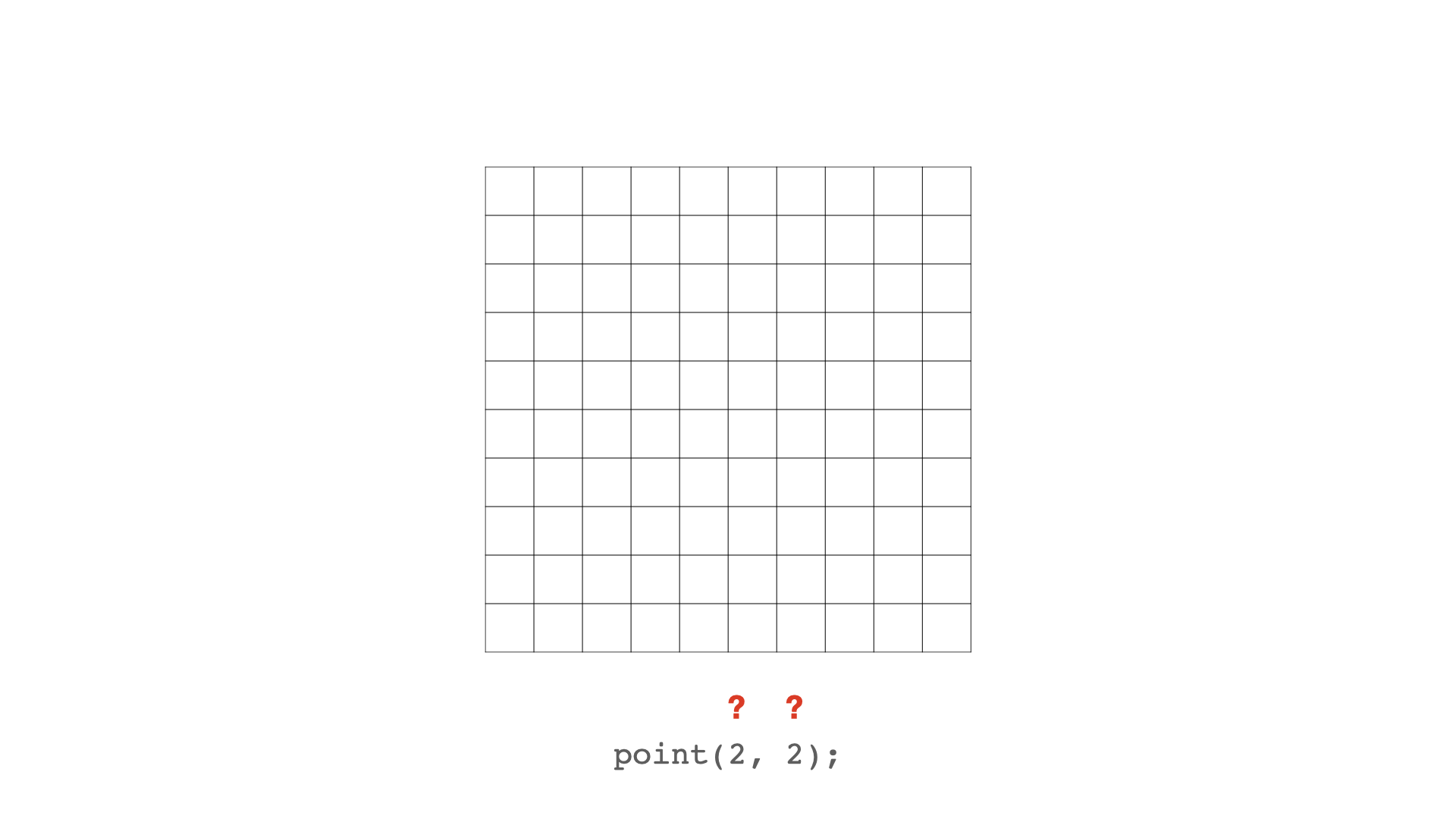

But what does (2, 2) mean?

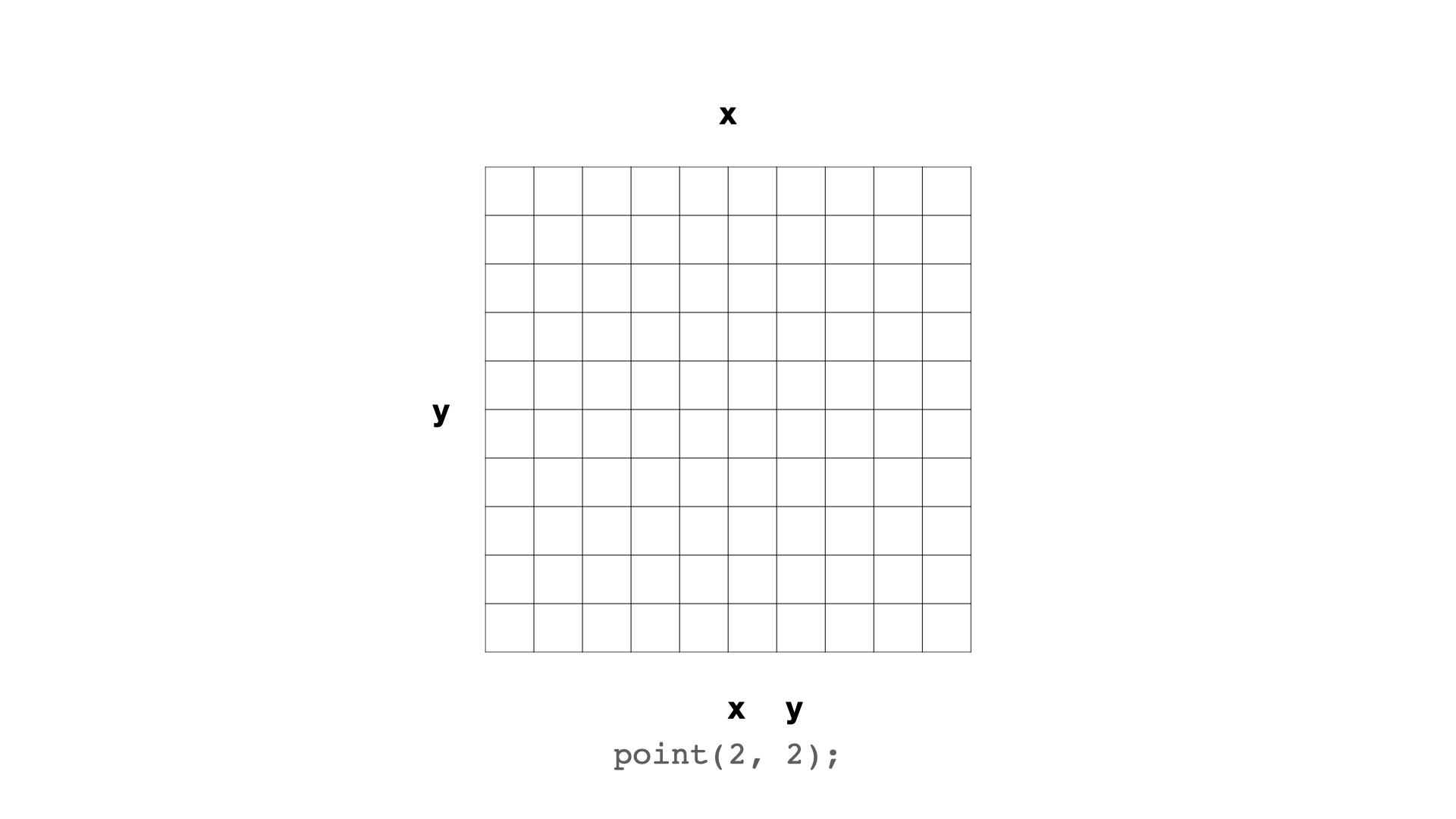

These are the x and y coordinates we want to draw our pixel at. The x coordinate tells us where to draw the pixel on the horizontal axis. And the y coordinate tells us where to draw the pixel on the vertical axis.

But what do those numbers actually mean?

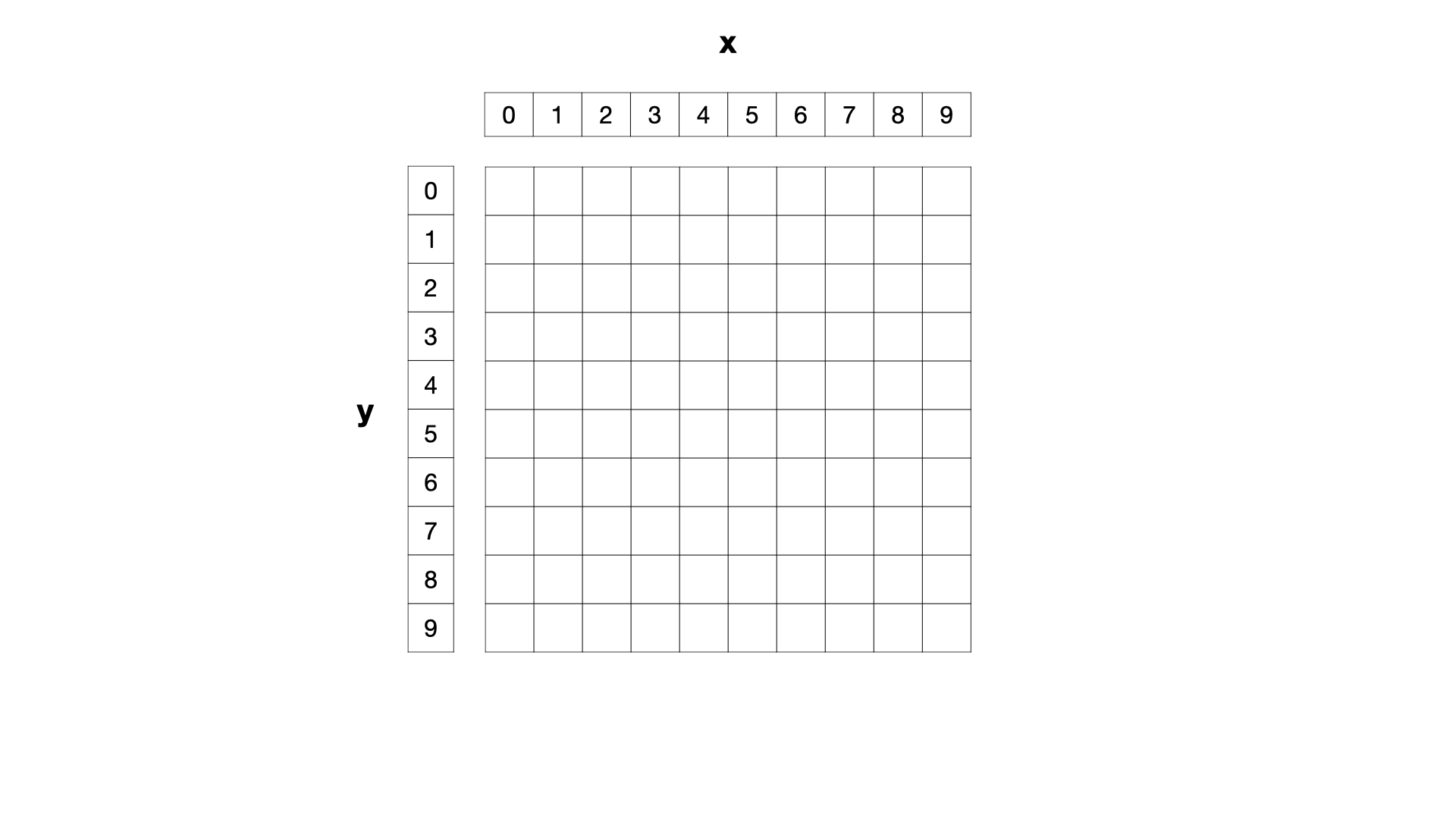

Well, the pixels on the canvas are actually numbered like this.

The x coordinates start from the left at 0 (not 1) and go up as you move to the right. So the 10th pixel from the left is labelled as 9.

The y coordinates start from the top at 0 (not 1) and go up as you move downward on the y axis. So the 10th pixel from the top is labelled as 9.

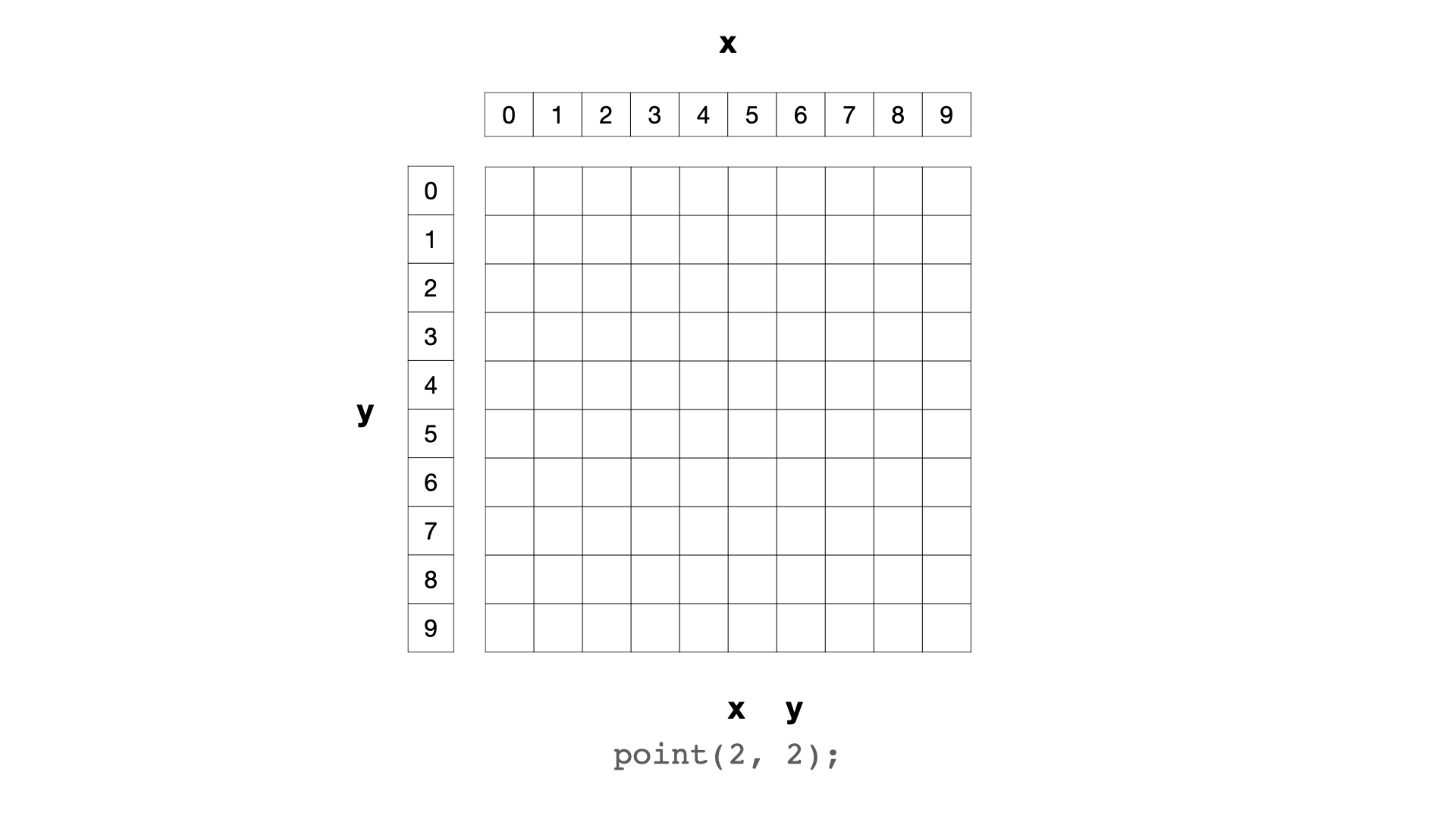

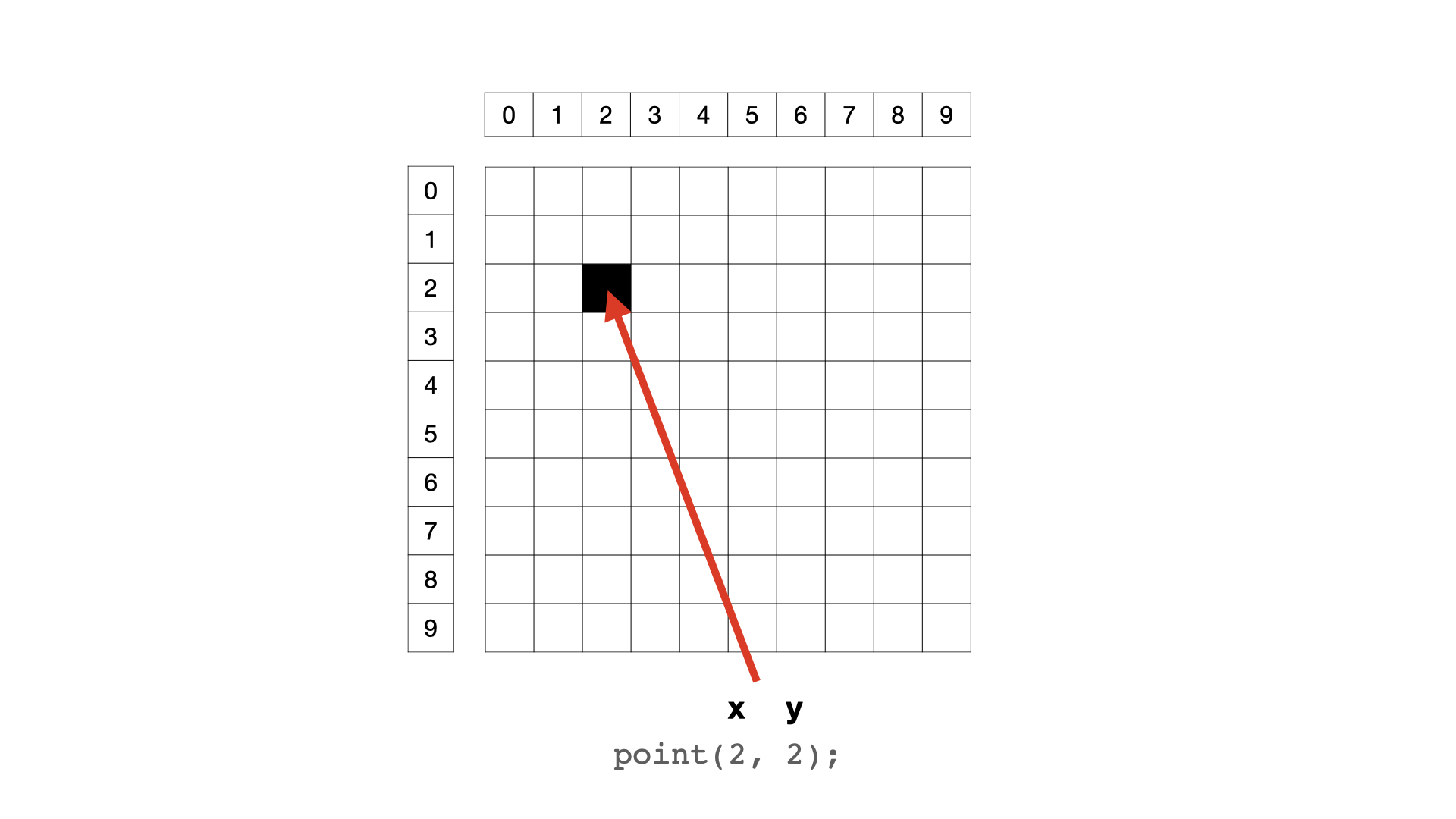

So, when we tell our program to draw a point (pixel) at coordinates (2, 2) we’re using that coordinate system.

And thus the pixel lands here.

A pixel positioned at (7, 2) lands here.

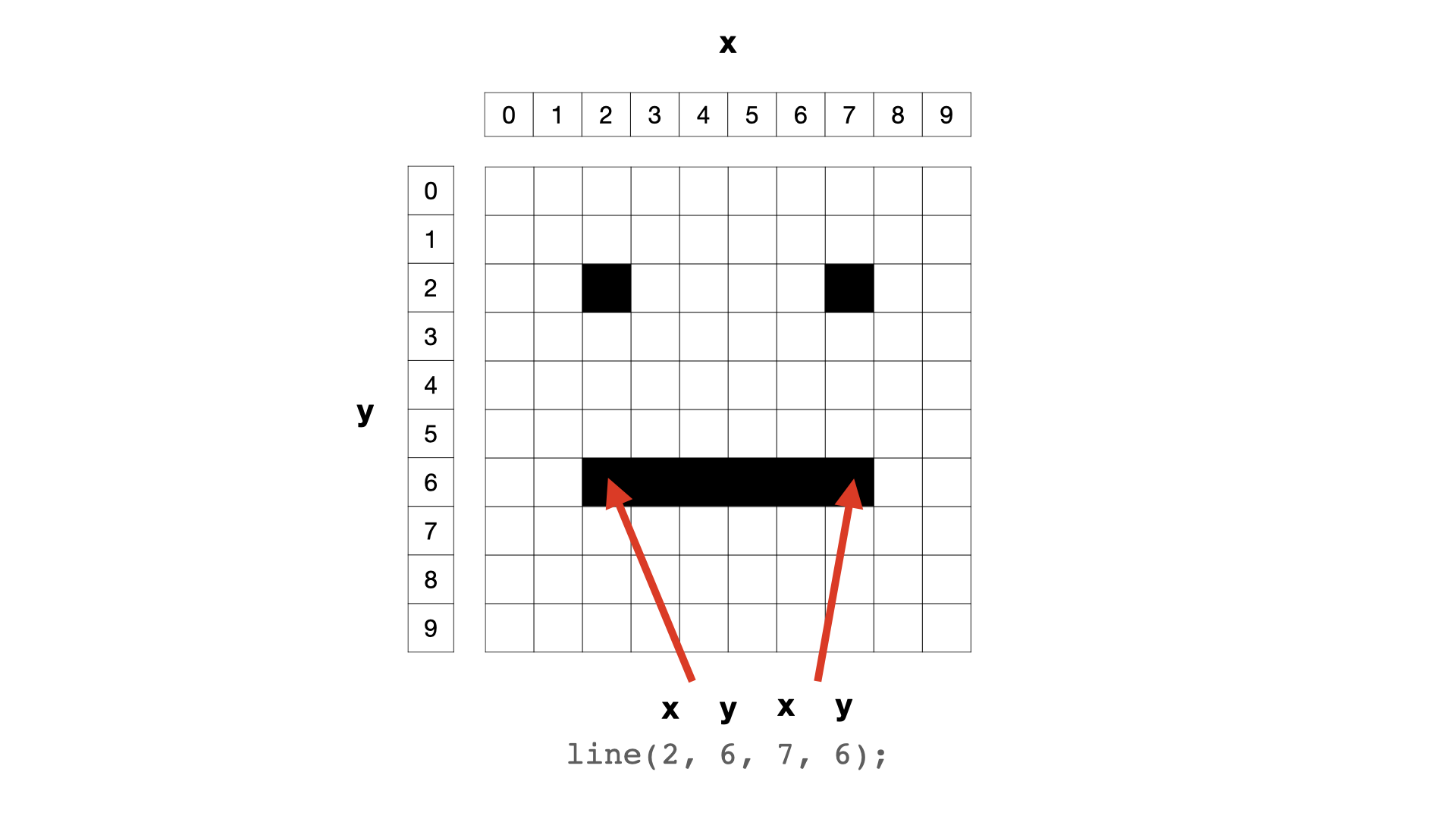

And a line from coordinates (2, 6) to coordinates (7, 6) will be drawn like this.

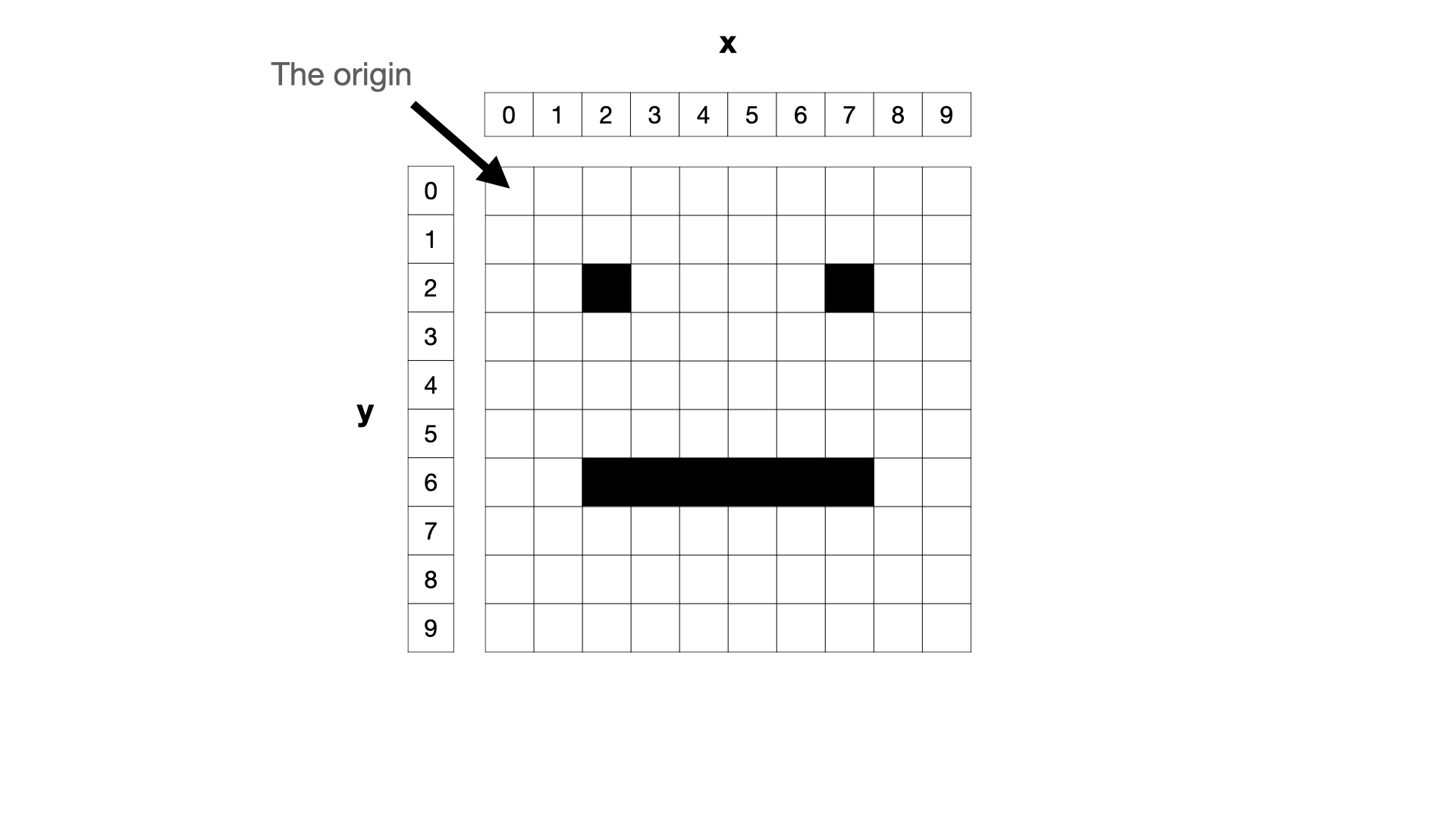

And that’s about it. Except that you should know that position (0, 0) is usually known as the origin.

Things are always being drawn relative to the origin.

Draw a rectangle

Let’s draw a square on the canvas so we can experience the majesty of one last function call with different arguments. Since we’re going to be drawing now, we’ll add it to draw() like this:

function draw() {

background(255, 100, 100);

rect(200, 80, 240, 320);

}

This is using the p5 function rect() to draw a rectangle in the centre of the canvas. Once again the function name and the arguments are different, but the basic shape of the function call is the same. It always is.

(Question: Why is it rect and not rectangle? Good question. Programmers often like “saving space” even though it’s almost always a bad idea for legibility. Sigh.)

So, what are the numbers this time? You can probably guess, but:

200: the x-coordinate of the rectangle’s top-left corner80: the y-coordinate of the rectangle’s top-left corner240: the width of the rectangle in pixels320: the height of the rectangle in pixels

If you check back in your browser you should see that the webpage has updated since last time (it’s Go Live remember) and you should see the rectangle.

Meaning

It does not take much for a program to mean something.

What if I told you that this is a program that simulates the experience of a writer staring at a blank piece of paper as they try to start writing their new novel. Well it does! And can you type anything? No! That’s part of it!!!

Play

Now would be a great time to play around the the numbers in the program. There are 10 of them and changing any of them will change the program. Can you make it mean something else?? Share your results!

Finishing up

- Commit and push the changes you have made in this session with an appropriate commit message

Summary

So we have done some real programming! In JavaScript! Using the p5 library!

Importantly, we have written three function calls that, together, draw a white rectangle with a black stroke on a pink background.

In doing so, we’re coming to understand the anatomy of a function call in JavaScript. The way we can tell our program to do something complicated (create a canvas, fill the background, draw a specific rectangle) only using a function name and some arguments. Power.

And we have given the program meaning despite its incredibly basic nature.

function setup() {

createCanvas(640, 480);

}

function draw() {

background(255, 100, 100);

rect(200, 80, 240, 320);

}

Next

Our program has already become complex enough that we need a way to explain it. That way is called commenting.