First thoughts (Tuesday, 22 December 2020, 11:12AM)

It’s been a fast-paced project. I started it officially yesterday morning and since then I’ve accumulated 11 nothings. That’s a whole lot of nothing.

Currently the big one I’m missing in the Unreal Engine, which I can’t install on my laptop as it takes up too much space. I can release this suite without it, but it does feel a bit fundamental, so I’m pondering ways to deal with that. Seems like Unreal does have a web export (community supported), so that would mean I could potentially create this version on the gaming laptop rather than install Unreal on this MacBook Pro.

It has felt nice to be so “productive” in terms of churning out different engines’ ideas of nothing. They do tend to differ in significant ways, which I’m glad of - it’s not just a series of blank screens that don’t tell you much. There is, unsurprisingly something there. Duh duh duh! Big reveal music effect here.

I feel like this project could be subject to a bunch of different forms of analysis, including some kind of code forensics, as well as the basic aesthetics of the nothing, as well as some of the signification of producing nothing, as well as the processual aspects of producing nothing. I can probably do some basic versions of all of these things here. It’s going to make the most sense to write an engine-by-engine review of the nothing experience I assume.

That’s a bit of a larger bite than I want to take out of it this morning, but I’ll perhaps write a bit about it later today or tomorrow while it remains at least somewhat fresh.

Twine and Inky (Wednesday, 23 December 2020, 10:32AM)

Alright well, as promised I thought I’d write some notes about the specific instances of Nothing I’ve created so far. I also realized a number of Nothings not yet made like Godot and Adventure Game Studio, so I’ll get onto those where possible. Anyway, on with specific notes, roughly in order of creation? Or no just in some order.

Twine, originally created by Chris Kilmas

Should I be listing specific version numbers of software? No I don’t think that’s all that important, this isn’t an archival effort, though it has a kind of archiving flavour.

Twine involved firing up the software and then exporting it to HTML. The project gets titled Nothing, which displays as the page title in the browser. The default Twine starting point has a single text node with default text in it “Double-click this passage to edit it.”. It displays in the default CSS, it has no links and is not interactive.

I quite like that there is content here and that the content explicitly references the process of making a Twine game, even if it’s an instruction the player cannot follow. It really marks the distinction between creation and play in a neat and tidy way, the ability to change the game versus the ability to play the game.

As with many of the Nothings, I like that it’s not nothing too, of course, and that’s a recurring theme. It’s not a blank page. As with any Twine, under the hood is the actually Twine JavaScript as well, so it’s a 295KB file despite being just some text on the screen. I don’t know enough about Twine to know whether the JS is reading data in from the page and then rendering it to the screen or not. When I inspect the page I see the same tags etc. so I think this particular passage, being the starting passage, is pre-rendered into the HTML, which makes the JS actually completely non-functional (except that it may well still be doing some stuff on startup anyway?). Looking through the minified code doesn’t tell me a lot - I can’t find a window.onload anywhere to most obviously suggest there’s code running from the very beginning, … oh wait, there it is. There’s an addEventListener for “DOMContentLoaded”, so it’s likely there’s JavaScript running on the page, even if it’s not “needed”. Such is life for game engines. They can’t know in advance what content you’re providing for them to interpret, so they have to try to interpret what’s there, even if it turns out not to need interpreting.

So, quite a lot of nothing going on with this one. I think the reveal of the inner part of the application through its default “Double-click here” message is really nice for this one. The creation application shows up explicitly (through language) in the played artifact.

Inky, by inkle studios

Inky isn’t a tool I’ve ever used to actually make something, though I’ve played a few Inky games I believe. The nothing in this case is just the word “nothing” in a pleasing font, representing the title of the “story”. Actually, this is true of Twine too to some extent, but there’s something worth noticing about the fact that in the context of this tool what we’re seeing is a story of Nothing rather than a game per se?

An immediately noticeable extra part here is that there’s a link at the top of the page “WRITTEN IN INK” that links to the “ink” page on the inklestudios website. So this is another way of referring to the tool of production, but more explicit, more like advertising. I quite like the accessibility implications of this, even if it’s perhaps not so artistically satisfying as a hermetically sealed story in a webpage. Someone looking at this story (or a less nothing one) gets to find the tool itself if they’re interested in crossing over.

The source code for the Inky version shows very simple HTML as well as linking to three separate JS files. There’s ink.js which is presumably the ink engine itself, obfuscated via minification. Can’t make much of it at all. There’s also Nothing.js which is interesting given that the story has no content at all. It contains the following:

var storyContent = {"inkVersion":19,"root":[[["done",{"#f":5,"#n":"g-0"}],null],"done",{"#f":1}],"listDefs":{}};

Most of that is mystifying (especially the #fs), but you can see it’s roughly speaking just the base level data structure for the story and contains almost nothing. Not nothing though.

main.js, the last source file, is not minified and is not super long and is even commented! Can see that a continueStory() function is being called to kick off the story, which presumably stalls out when it finds out there’s no data. It’s interesting how little code there seems to be here in the main script to drive the engine forwards - feels like a neat package, all the action is in ink.js I guess.

Also of note with Inkle, the software I used to make this, is that I couldn’t export the “nothing” it starts out with. The program loads with a blank page, but I couldn’t export it to HTML until I typed a character, saved it, deleted it, and saved it again. So there was this sense I had to really consciously signal I wanted the nothing that was already there. Raises the question of whether it’s still “nothing” if I had to exert this particular effort to get it to a releasable state, even if that state is (roughly speaking) the same as the starting state? Is there a ghost of that character (I think it was an “e”) that I typed hovering over this project?

Bitsy, flickgame (Wednesday, 30 December 2020, 12:36PM)

Bitsy, by Adam Le Doux

I’m a major Bitsy fan of course and used it to make b r 1, Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment: Bitsy Demake and b r 3.

As a nothing it’s one of the more something ones. The default setup (care of Adam Le Doux) involves a simple avatar, a room with walls, and a cat that says “I’m a cat” when you walk into it. This speaks to the accessibility of the engine and its general attitude of friendliness (a cat!). This way it provides examples of a large amount of functionality in a really simple way. It also includes a cup of tea, though for some reason that’s not positioned in the scene by default so you don’t see it in the nothing, though I presume it’s in the underlying code? Just checked and yes. In fact there’s a “key” in the underlying code as well. At any rate, the way this “nothing” is designed is to bring people into the experience super fast - you could just redraw a couple of things and begin to have your own understanding of the tool but also your own aesthetic stamp on it. So the tool doesn’t emphasize its (quite significant) possibility space (as other engines like Unity do by kind of giving you just nothing, a void with a horizon) in favour of being accessible and non-threatening.

Like pretty much every engine, there’s a ton of code underneath the “nothing” that represents the engine itself which could do a bunch of stuff if there were more data to crunch. As it stands there’s data too, but it’s the default data for the wall, cat, avatar, key, and room. In the end this nothing is 196KB, which ain’t nothing.

flickgame, by Stephen Lavelle

This is Stephen Lavelle’s ultra-accessible game engine in which all interaction is based on hyperlinks which are based on colours. So you have clickable bitmaps where specific colours lead to new scenes/pages. And that’s it! It’s beautifully simple conceptually.

The nothing is just the default scene, which is quite delightfully a dark aubergine kind of colour. I like that it isn’t black or white or something other more “neutral” colour, it indicated a personality despite its extreme blankness. You can’t click the colour to go anywhere because there’s no link programmed in.

In a testament to the simplicity of the engine, the HTML file is a mere 17KB, almost certainly the smallest of the nothings (well except for the blank PDF print-and-play). In the HTML there’s some initial CSS, and then a dataset which I suppose I’d assume is a listing of the colour of every pixel in the one scene that there is? There are a lot of 0s, which you would think would mean black, but maybe it means “blank” in this context? In the end I can’t really tell without seriously getting into it, which I don’t think I’m up for right now. I could also ask Stephen, but I think it’s okay if this remains a mystery at the moment.

It still takes a pretty decent amount of JavaScript to make this whole thing work, and it’s not obfuscated which is quite nice - you can genuinely read and understand it, though it’s uncommented (for size reasons I’d assume). It’s also written entirely in plain JavaScript with the DOM rather than using an extra library like jQuery or similar.

PuzzleScript (Thursday, 31 December 2020, 12:30PM)

PuzzleScript, by Stephen Lavelle

Somewhat like Bitsy, PuzzleScript provides a fairly detailed template as it’s starting point, with a little Sokoban level to solve if you run it. To this point it’s the only “nothing” that represents whatyou might think of as a playable game, even having a menu and a win condition. It’s not the world’s most complex game (push the right arrow three times to win), but it’s a proper game with underlying mechanics and so on.

For that reason it’s pretty interesting that the actual PuzzleScript source for the game is really, really simple. Presumably this is the point, to demonstrate the ability to make quite sophisticated gameplay with minimal effort (or at least non-length effort). The PuzzleScript source is 69 lines long, commented, and quite intelligible. This is interesting at least in part because it demonstrates a really concerted separation of gameplay and level design I suppose? With the ruleset provided (moving crates onto targets) we know that you can make the entirety of Sokoban, with arbitrarily complex levels, some of which could be insanely hard to solve etc, when in the underlying source they’re effectively just diagrams of levels, with the complexity baked into their arrangement of elements.

PuzzleScript being implemented in the browser, it’s actually a higher order language on top of JavaScript, so in this particular nothing you of course end up not just with the PuzzleScript source but the source of the PuzzleScript engine on top. In this case the engine is obfuscated through minification to reduce the file size, and it still only comes in at 296KB which is kind of impressive for an entire engine! (Godot is in the background downloading some 400MB template file just to be able to export anything right now, that’s over 1300 PuzzleScript engines). It’s not actually as easy as I’d expected to find the source of PuzzleScript (it’s not obviously linked from the running engine itself), but it’s easy enough to google up: https://github.com/increpare/PuzzleScript. I’m not going to go through the source code itself, but it’s interesting somehow that this repository is representative of the “nothing” I have in this suite, just in an expanded and (much) more legible form.

So the aesthetics of this nothing are very detailed, very not-nothing, and very educational in terms of the engine. They show you the most obvious kind of thing to make with it (Sokobans) and they provide a tiny use case along with its source to help you understand basic possibilities.

PICO-8, presentation (Friday, 1 January 2021, 14:05PM)

PICO-8, by Lexaloffle

This was one of the more complicated nothings to produce because the PICO-8 system itself has a learning curve just to understand how to export anything at all. I also had to buy the “fantasy console” to get going, because although I did have a copy already (somehow? from the Old Days?) I wanted to get the latest version and couldn’t find any record of having bought it.

Loading up PICO-8 just gets you a command line, so I ended up having to look a bunch of stuff up in the documentation just to create the basics. That mostly meant creating a new .P8 source code file and making sure there was nothing inside it, then figuring out how to export that file as HTML5, which also involved needing to take screenshot for the thumbnail. Though as I sit here I’m thinking: why did I do that? Then I remember that it’s because it literally wouldn’t export without the thumbnail and that is why I did it. Rather than take a screenshot at the precise moment I needed it (perhaps more authentically nothing) I took it of a “blank” screen in the command line. I feel lightly troubled by that aspect of my process.

Experientially the nothing involves the screenshot with a play button on it. When you his play the console loads and does a little flashy intro thing, then gets stuck on “BOOTING CARTRIDGE...”. I can’t tell just by look at it whether there’s some internal error in the console caused by the cartridge (source code) being empty, or whether this could be considered the correct behaviour for the console. You load the nothing and then the nothing issues no instructions to get you beyond that loading moment? Hard to say without looking deeply into the source code of PICO-8 itself.

Exported, you end up with an HTML file and a JavaScript file. Quite substantial, both, that JavaScript especially. It’s 1.5MB in size, not nothing at all. I guess it’s a whole fantasy console in there, doing nothing. I guess this makes me think, in this moment, of this idea present in most of the nothings of potential unrealized - complex structures of code sitting idle or almost idle, paths unfollowed, computation uncomputed. All very poetic and pathos-filled.

Presentation thoughts

A quick note because it’s been circling my mind: it feels like it would be nice to tie writing about this project more closely to the individual nothings with some kind of “discussion” link per nothing that would have a fairly accessible run down of what I think about it? Probably in the vein of the writing above, but tidied up to be a bit more readable etc., maybe with some specific links to commits or files in the actual repo and so on.

And that makes me wonder more generally about surfacing some kind of accessible rundown of each project. Not quite the Closing Statement thing, but perhaps replacing it or something. An accessible summation, separate from any more “academic” write-up I try to do. or maybe you don’t replace the discussion but instead right a shorter, more thrifty explanation of what went on and why?

Anyway for now I just want to flag this is a thing I want to think about and try to include in this overall project.

Inform 7 (Saturday, 2 January 2021, 12:37PM)

Inform 7

I’ve used Inform 7 twice now, once for Kicker and once for the Text Adventure edition of Let’s Play: Ancient Greek Punishment. I’ve never found it to be an easy language/environment, it’s full of weird things you have to understand and weird (to me) ways of expressing ideas in almost natural (but ultimately quite unnatural) language. I vaguely wonder whether a more standard programming representation of the same underlying structures could be easier quite frankly. The spectre of natural language makes it a bit easier to get things wrong for me, because it prevents me from thinking in terms of more rigorous syntax.

To produce the nothing was relatively straightforward. It was one of the first I went for and as such was part of my debate about whether “nothing” should be represented with empty source code where applicable. Inform 7 is one of those engines that simply doesn’t compile without some basic content (you have to have a room). When you load a project it does have a standard “example room” all present and accounted for, though, so you can export that. I took the liberty of explicitly naming the project “Nothing”, since that’s been a consistent theme across the project, but it’s perhaps a little dodgy given that this is a case where it’s optional. Although now I go back and look at the process I see that when you create a new project you get to title it on creation. Initially I’d kept the default (Untitled), but these days I title the project Nothing each time for a bit of completeness. It also auto-adds my authorship which I think is kind of interesting.

The entirety of the source is:

"Nothing" by Pippin Barr

Example Location is a room.

Which is pleasing in its blankness and also its non-nothingness.

Inform 7 turns out to be one of the more interesting Nothings for me for a couple of reasons. First (maybe less interesting) is that I found out I couldn’t export to HTML5 even though the engine is capable of it because to do so requires adding to the source code - it’s in Inform’s nature that you do almost everything through language in its source, rather than through menu options for example. So to export as HTML you need to add

Release along with an interpreter.

But of course that’s no longer the same Nothing that you begin with. It does raise the question of whether even exporting these things is some kind of rule violation, or whether exporting them in a “non-native” (whatever that means) format is some kind of rule violation. Of course, I’m making the rules here, and it seems legit to me to export, for example, Unity in WEBGL. But it raises some kind of question about the difference between doing that with menus and doing that with text inside the source code. I guess my rule is just that there shouldn’t be alterations of the source, pretty fundamentally. In a way, it’s a data-oriented view of nothing: no additional data added by me (except the title).

So the end result of not adding the interpreter line is that I can’t release the game in any form except a .gblorb file, which can only be used with a separate interpreter. I think that’s kind of fun, that it also invites you, in a way, into the larger world of these kinds of text adventures. Playing the nothing gives you something that would let you engage with IF - an interpreter.

The other thing that is maybe more interesting is that way that the nature of Inform 7 as an parser-based system exposes all the potential that exists in a way that other engines do not. Most of the Nothing end up loading some kind of static, non-interactive experience of one kind of another. Because Inform 7 is interpreted there’s a ton of built-in response (that you would normally override) to all these built-in verbs you can use. In the example room you can kind of run, look, jump, sleep, etc. etc. etc. It builds a very definitely sense of presence in this nowhere. You can look at the room you’re in, for instance, and see literally nothing (not even text saying you don’t see anything). You can hug yourself. And so on. So it’s a way of showing all the stuff that’s built in - it still serves as a way to explore Inform 7 itself and its default possibilities, or at least a number of them.

For what it’s worth the Nothing.gblorb is 604KB. Not huge, not tiny. I suppose that tells us something about a division of labour between what the interpreter software would do and what the story data is composed of. I’m a little unclear on what’s going on in there, though, as the .gblorb isn’t human-readable. Clearly it’s more than just a representation of my source code. Perhaps it’s a representation of all the default possibilities an Inform 7 game has?

Anyway, Inform 7 is definitely one of the interesting ones, huh?

Ren’Py, Godot (Monday, 4 January 2021, 10:26AM)

Ren’Py

I was interested to look at Ren’Py because it’s definitely part of my consciousness, I suppose chiefly because of that Dating one called…? Save the Date, that’s right. Anyway, that’s what I know Ren’Py as to some extent, but more generally than that I think of the visual novel thing as both very alien (I bounced off the few I’ve tried pretty hard) and as important/super popular. So, “using” Ren’Py would be interesting.

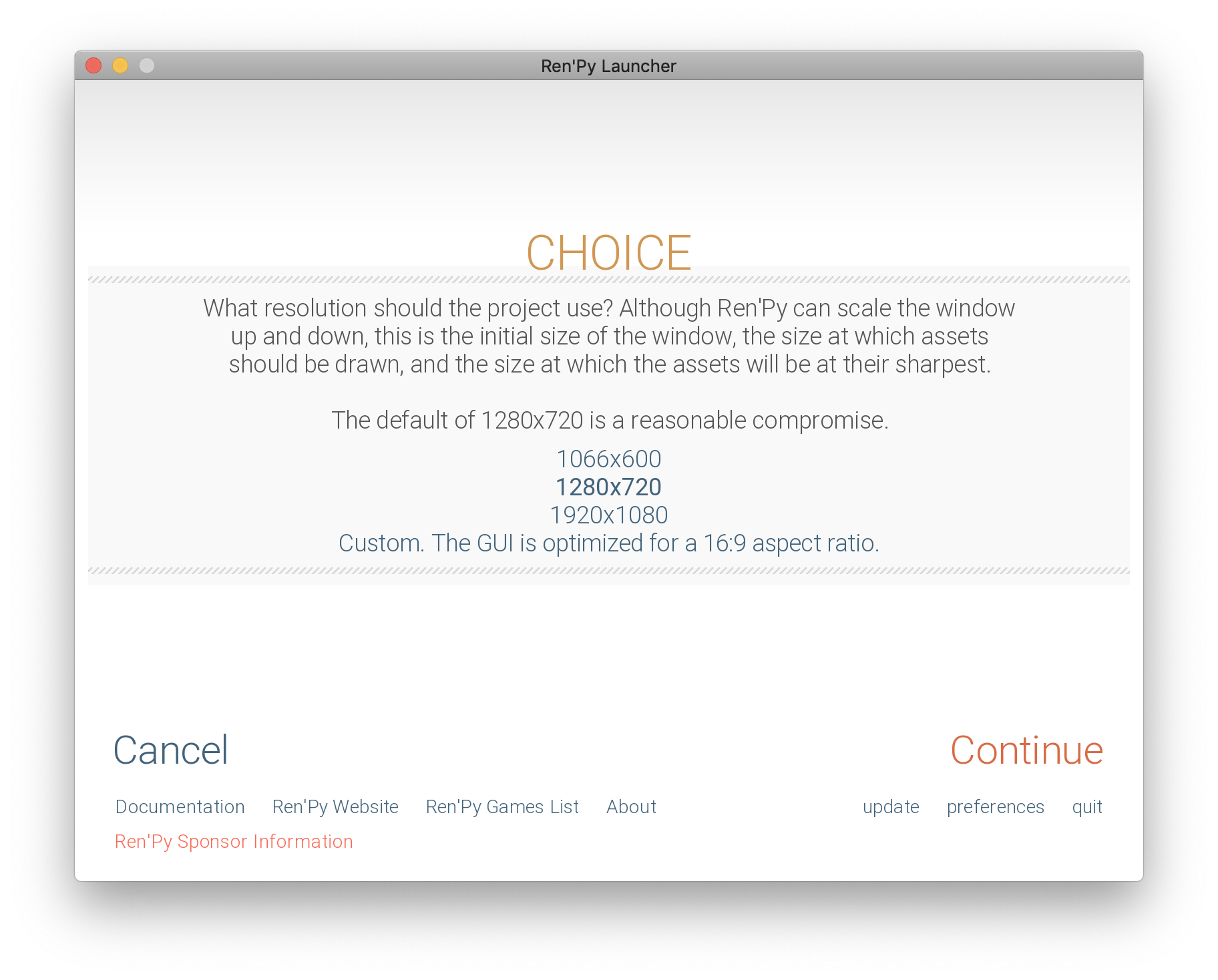

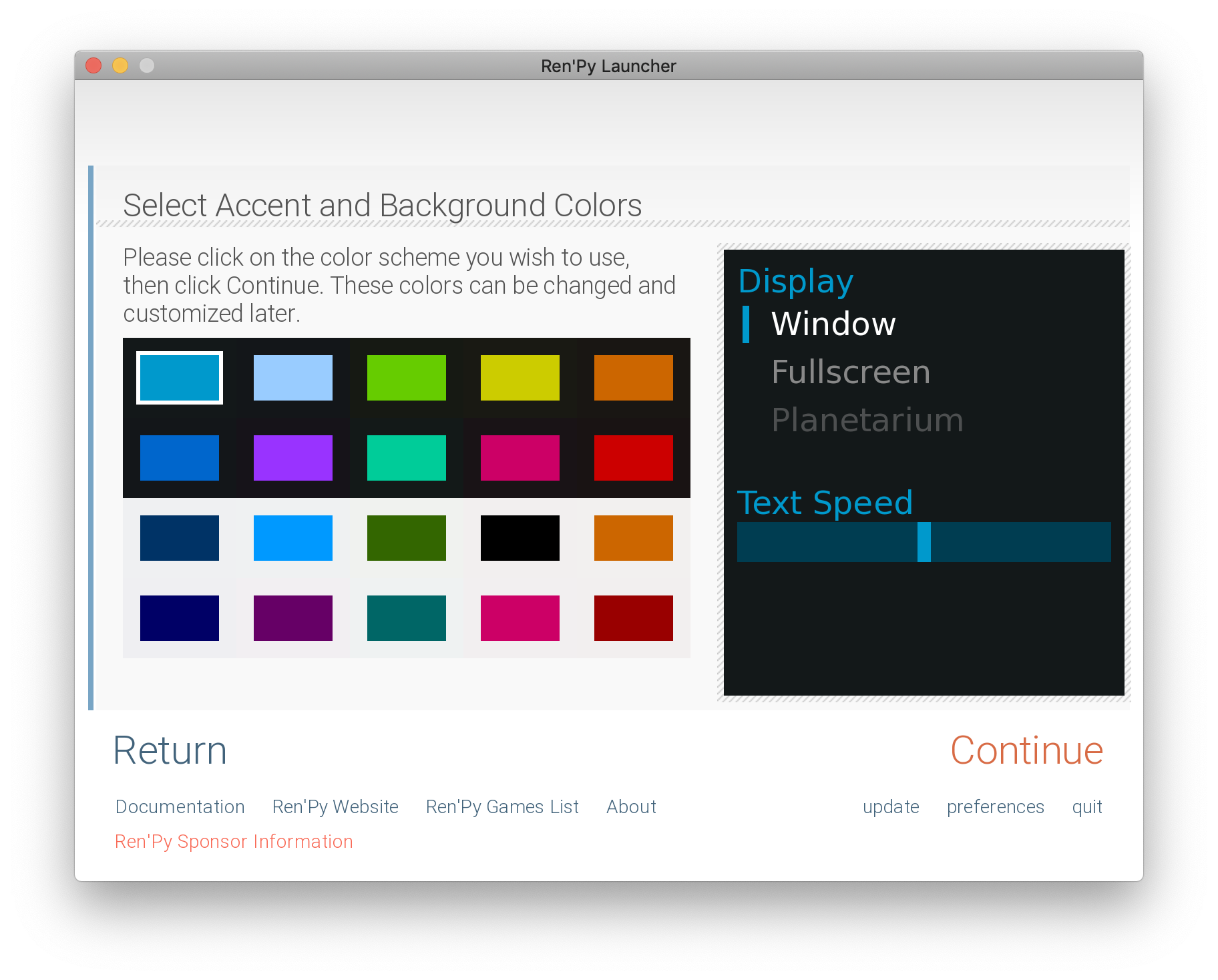

However, in creating the nothing it pointed out another element of all this, which is that making nothing in an engine doesn’t necessarily tell you very much about what it’s like to use the engine to make anything. To make nothing in Ren’Py was a bit of a process with multiple setup screens like these two:

Selecting a resolution

Selecting a resolution

Selecting a color palette

Selecting a color palette

But after that it exported without much difficulty on my end. Because I didn’t really engage with producing any content, I really have no idea how you make anything in Ren’Py. This is different to my experience with something like Inform 7, for example, where I know a bunch about the underlying framework of the engine and what it provides, so I can kind of sense the depth of the nothing. With Ren’Py I really can’t.

In terms of the experience of the resulting nothing, it’s pretty elaborate! It first loads stuff with a little loading back and even downloads and extracts a specific data file (with my nothing in it I suppose). There’s a big splash screen with “Ren’Py loading…” and a woman holding a globe in her hands. Very elaborate and very, very specific aesthetic. I assume you would replace this stuff if you were making something for real, but it’s interesting that it’s in there and tells us some things about the basic expected use/genre of Ren’Py. Once loaded, you get an entire menu system for “Nothing 1.0” including the ability to Start, Load, set Preferences, read About it, and get Help! This is a ton of functionality I didn’t put in there, all placeholder.

Help gives me some default guidance on keyboard commands within the Ren’Py reader. The About contains a reference to the specific Ren’Py version and some licensing information. Preferences lets me set a ton of reading preferences. Load lets me load notional saved games. Start lets me start this one…

When you Start the nothing you get a couple of overlapping red errors at the top due to files I haven’t provided, which is kind of interesting - they have no default provided so you get actual problems right away. You also get some dialog from a character called Eileen who’s saying placeholder text about how I’ve created a new Ren’Py game and how I can add the story and pictures and then release it to the world. Then the game ends. At the bottom while the story runs are a host more menu items including saving, skipping, preferences, etc. There is just a ton of framework around the core of nothingness I provided. I guess this tells us just how structured Ren’Py is, perhaps more than the other engines I’ve looked at it has really rigorous expectations for how things will be and builds a larger set of tools than something like Twine. It’s more “professional” in that way?

In terms of the source itself, there are a lot of files involved in this and the overall directory of Ren’Py stuff is 8.4MB, so quite significant given it’s an empty experience (sort of). I sort of feel overwhelmed by all the different components here, the lion’s share of which I suppose are based around getting Ren’Py into HTML5 form. There’s no easy-to-read instance of the “nothing” data I actually provided to the game.

Godot

Godot is one of those important engines that I would in principle like to use or have used, but haven’t because I already learned Unity and don’t have the energy or virtue to learn Godot properly. Or something along those lines. Really enjoy that it’s Open Source and noble. As with Ren’Py, just producing a nothing with it didn’t tell me much beyond a very quick glance as its basic presentation on load and then a fight to get it to export.

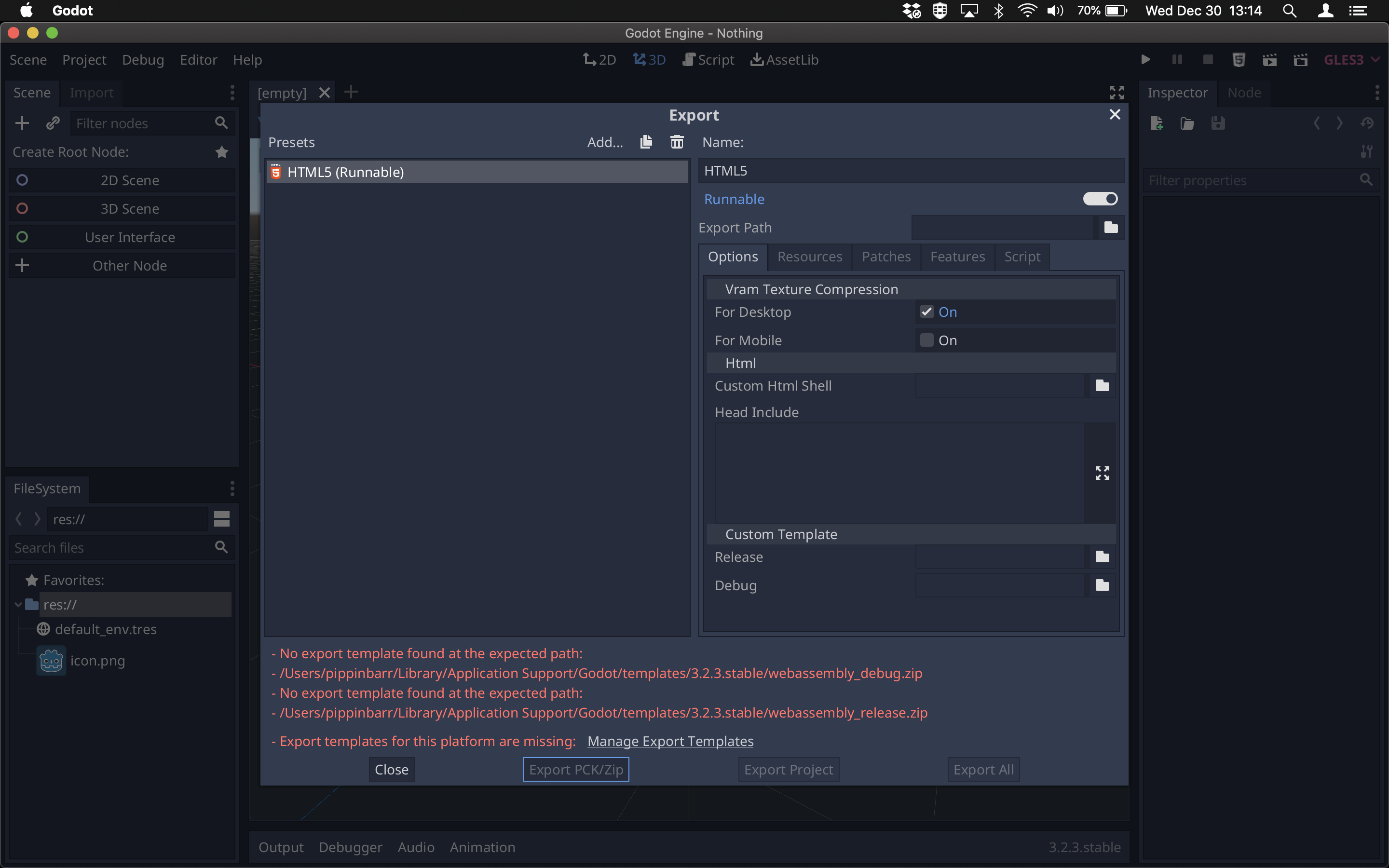

In particular, just trying to immediately export to HTML5 turns out not to work because you don’t have a “export template” installed:

Easy enough to fix with a 400MB download(!) and then the nothingness is exported successfully as a mess of files. Because I exported into the working directory I was building the project in, I can’t actually tell which of the files are part of the exported HTML5 nothing versus the Godot project Nothing. I guess I should untangle them. There I did that, so Godot leaves me with five files in the end, most of it in JS and then a .wasm file which is huge at 20.5MB for some reason - I assume that kind of the WEBGL player for Godot? Looks like WASM stands for WebAssembly? Which is a way to run things in the browser that are not strictly HTML/CSS/JS stuff? I really don’t know. Apparently Unity uses the same basic technology for its Web Player as well. The upshot is that the Godot thing is a big one.

However it also fails in the console of the browser, announcing:

Error: Can't run project: no main scene defined.

and then failing with an actual error:

Uncaught RuntimeError: function signature mismatch

at StringName::StringName(char const*) (<anonymous>:wasm-function[532]:0x2a4b3)

at OS_JavaScript::initialize(OS::VideoMode const&, int, int) (<anonymous>:wasm-function[37976]:0x95f2a2)

at Main::setup2(unsigned long long) (<anonymous>:wasm-function[54399]:0xb56d5e)

at main_after_fs_sync (<anonymous>:wasm-function[24161]:0x5e7e07)

at Module._main_after_fs_sync (http://127.0.0.1:3000/Nothing.js:8:323869)

at ccall (http://127.0.0.1:3000/Nothing.js:8:9246)

at http://127.0.0.1:3000/Nothing.js:8:23977

Presumably this is the same kind of error expressed in code, where there’s just no scene for it to load? Hard for me to say though, definitely out of my depth with that. It’s interesting, though, that unlike Unity, Godot doesn’t provide a default scene when you create a new project. So unlike Unity, which gives you a semi-pleasing view of a horizon, Godot gives you nothing and an error. Decisions decisions.

Print-and-Play (Monday, 4 January 2021, 20:21PM)

Print-and-Play

I mean, I don’t want to sound too clever, but I thought having an analog nothing was pretty fucking good okay? I thought of it in a bath and I felt so very pleased with myself. Created by firing up Microsoft Word, using the Blank template, and exporting to a PDF. One of the smaller games at 12KB.

Quite enjoy the implication of the download link that what you’re getting are instructions for playing a game called nothing. I suppose at a huge stretch you could say there are no rules and thus total space for imaginative play etc. This is the easiest one to call “not a game” given that it has no game form whatsoever and no obvious game potential baked into the “engine” of a PDF/text document.

I like it. It’s probably not the most profound or interesting in terms of theory, but I think it’s the funniest and that counts in my books.

Construct 3, Stencyl (Tuesday, 5 January 2021, 10:03AM)

Construct 3

Another engine that I’m not personally familiar with. Construct turned out to be pretty seamless in terms of exporting a nothing - the actual app exists online, it exported happily enough. There’s not even a commit message of interest around how the process went and I literally cannot remember it to speak of. Guess I just ran Construct 3, started a project, and exported it to HTML5. Kind of embarrassing from a process standpoint.

The most memorable thing about the Construct 3 process is that when I ran the Nothing locally it horrifyingly kind of took over my local host and would run when I was trying to run other stuff (like code I was writing for my upcoming class). It has some very sticky offline mode stuff that was annoying to get rid of, and actually involved me deleting two files from the export, making this not the most authentic nothing because I actively removed its offline mode. But it’s just so hostile and gross I don’t want them in there in case I accidentally run it again and break everything.

That said, there’s something quite interesting/nice about an offline-available nothing, so I’m a bit sorry to miss that special feature.

The experience of the Construct 3 nothing is pretty standard: a loading screen (“Powered by Construct 3”) followed by a blank white canvas. My removal of the “service worker” for the offline mode leads to an error in the console that wouldn’t otherwise be there. The whole package is 1.2MB (without those two files I removed).

Frankly it’s a pretty boring one. I feel like Construct 3 just didn’t have a lot of material, not much to say on the nothing front.

Stencyl

I always think of Stencyl and Construct 3 as semi-identical, though I’m sure there are proponents of each that could give me a reasoned argument about how they are super different. That’s okay. Stencyl was similarly unremarkable in terms of just exporting successfully and yielding a similarly underwhelming nothingness composed of a loading screen and a blank. The Stencyl loading screen is unbranded which is kind of interesting, nothing about it tell you that Stencyl was the tool used, it’s just a little loading bar on dark gray. When it’s loaded you get a totally blank page, white, with a white canvas on it and nothing happening.

In terms of the underlying source and files, Stencyl’s nothing exports in a pretty organized way with an assets folder, a lib folder, an HTML file, and a JavaScript file. 1.5MB in total.

Yeah I mean, just not a lot to write home about? Kind of feels like this fits or is reflective of the personality of this tool (and Construct 3)? Just sort of effective and a bit boring, a bit unassuming? I don’t quite know. I guess in presenting themselves as real multipurpose tools there’s this idea that the blank template should be totally blank and not suggestive?

I’m just running Stencyl again to examine the process of exporting a nothing. You “Create a New Game” and then choose a template, and the only template that’s there by default is “Blank Game” where you “Start from Scratch”, so that’s what I did. There’s a Platformer example project included with Stencyl, but it’s not offered explicitly as a template.

Unity (Wednesday, 6 January 2021, 15:51PM)

Unity

Unity is certainly a platform I’m familiar with, having made various games in it and taught it in a game design course. It’s not necessarily my favourite engine to work in for accessibility and heaviness reasons, but I’ve always found it pretty fun to work with and I do have a soft spot for 3D.

Creating my nothing in Unity was straightforward in that I just created a new project, added the default scene to the build, and then exported. There was a brief snag when I realized the version of Unity I’d launched didn’t have the WEBGL export package installed and I had to restart with one that did (life with Unity Hub), but beyond that it was uncomplicated.

The resulting nothing experience has a single camera pointed at the horizon of a skybox. It’s genuinely kind of peaceful and, for me, iconic of what nothing means in the context of game engines. That static skybox is quintessential nothing. Oh I guess there’s a directional light in the scene too, by default, but it’s not really illuminating anything (except I guess controlling the default dynamic skybox presumably). Totally non-interactive, just a “view”.

As I’ve worked with it plenty, I know all the latent potential the nothing isn’t using, but I definitely don’t know to what extent the build itself excludes all kinds of code and potentials because it can tell they’re not being leveraged. The resulting project folder with the WEBGL build in it is 3.5MB, which really isn’t very big and would lead me to think that it’s a pretty stripped back version of what Unity can do. Does it have the potential to move the camera? Probably? Does it have the potential for wind or reflection probes? No idea. Does that even mean anything in the absence of using those things in the project? Don’t know. It’s pretty mysterious to me.

The WEBGL build also includes some little bits of interface stuff, including a loading screen and a fullscreen button and a Unity logo (that doesn’t link to their web page oddly). When the load finished you see the classic “Made with Unity” splash and then the static scene after that.

I’ve debated whether or not I should be providing Windows/Mac/Linux builds of the nothing, whether that would signify anything particularly important or not. Currently I don’t believe I care enough to do it - it would make some kind of point about distribution and cross-platform stuff, but it doesn’t feel so important. To me the core is what the actual “player experience” of each nothing is alongside any processual stuff to produce it I think.

Unreal Engine 4 (Wednesday, 6 January 2021, 15:51PM)

Unreal Engine 4

I don’t have Unreal Engine 4 on my computer - I started to install it but it was so huge that I frankly just gave up at the point it told me there wasn’t enough room on my drive. Unreal does figure in my imagination around game production because it’s always the “other” engine to Unity for me (as Unity is for Unreal people I suppose). It’s also the engine a lot of students tend to say they really enjoy using and, at least at one time, that was the idol of graphics chauvinists.

Because I didn’t have the engine I contemplated just not including it, but it feels like one of the ones I wouldn’t want to miss, so I asked on Twitter for help and received it in the form of Andrew Baker.

I’ll include our entire conversation about the process here for reference!

Pippin

Dec 22, 2020, 7:06 PM

Hey there! So the genuinely tiny project in question is to make… nothing. I’m interested in you starting unreal and then just exporting whatever is there by default, if that’s possible with that engine. Titling the project Nothing. As I said if we can do a web export so much the better, but downloads okay too, and perhaps more “authentic” anyway?

Andrew

Dec 22, 2020, 9:28 PM

Do you mean literally empty? Like, not even a camera? Because I could just make a black rectangle png and tell you it’s an empty project’s web export ;)

Dec 22, 2020, 9:29 PM

How about good old Blank?

Pippin

Dec 23, 2020, 10:18 AM

Haha, you can’t get a black png past me!

So Blank is a project template option when you try to start a new project? Sounds perfect. Yeah, the idea isn’t to delete anything, just to release exactly what “nothing” looks like in the engine. Blank makes sense for that.

I love that “blank” appears to have a floor?

Andrew

Dec 23, 2020, 1:37 PM

Yes, and the default pawn is a free-flying pawn.

Here is the link:

... Sends file NothingHTML5.zip

It took an embarrassing amount of effort to create a viable “Nothing” project with UE4.

I verified that it was working in Chrome prior to uploading it.

Dec 25, 2020, 7:27 PM

Yo, Pippin! Please let me know what you think.

Pippin

Dec 25, 2020, 9:51 PM

Hey Andrew - apologies, caught up in the Christmas spirit etc. I’m curious about the specifics of the effort! What did you end up having to do? Hopefully nothing in terms of actually changing anything in the Unreal editor itself? In terms of the project I’m happy with whatever it spits out when you export a project based on Blank…

Was it just the HMTL5 export stuff that was a pain? It looked a little painful from a quick glance…

Dec 25, 2020, 9:52 PM

Just ran it - looks great. So damn weird how involved that is for “nothing”! Kind of great. I guess all the menu stuff is from the HTML5 export. I wonder if I can ask you for a Mac/Windows downloadable? (Also fine to say no!)

Andrew

Dec 25, 2020, 11:15 PM

Oh, shit, yeah, I forgot that it’s Christmas day. Time has lost all meaning for me.

It wasn’t too bad, I just had to convince Unreal Engine that I really, really wanted to do the thing I wanted to do.

Yes, the weird UI stuff comes with the HTML5 export.

I’ll get a Windows 64 download for you pretty soon.

Dec 25, 2020, 11:17 PM

And then, I’ll try to get a Mac export after that.

Dec 26, 2020, 7:47 AM

Here’s Windows:

... sends file NothingWindows.zip

I don’t think I can export a Mac build without some iOS developer gubbins:

Pippin

Dec 26, 2020, 12:19 PM

Yeah, Apple is just so helpful like that. No problem - if I get to it I can probably install Unreal myself and do this (but I really like the idea of this Nothing being a collaboration!).

In terms of Unreal and the Nothing - if it’s not too boring can you go into some detail about the process? The majority of my rationale for this project concerns that specific process - what does it mean to create nothing in different engines, so I’m genuinely quite interested in what that process looks like for Unreal, and I’m curious about this idea that we’re collaborating and so there’s a step removed for me where I need to hear about it from you.

In particular, just wondering which bits of it felt like they were “extra”, which parts of the engine might have “resisted” making that nothing. Mostly the web export component? At least in Unity it’s fairly easy to export nothing - you just start a new project and immediately build and export it - so I’m interested in how Unreal might have been different on that front! (Also if you’re up for it, I’d quite like to include this “correspondence” about the project in the process documentation.)

Andrew

Dec 26, 2020, 2:00 PM

Even though the template starts with a valid placeholder level, that doesn’t exist as a real file until I saved as a real new file. Then, to get it into the exported game file, I restarted UE4Editor, and then picked that level as the gameplay default. The level was auto-picked in the gameplay default upon creation, but it didn’t “take” until after the restart.

Yes, this conversation can be published in its entirety.

But, the thing I was most cautious about was doing as little as possible.

I didn’t want to make a fake Nothing.

I can send you the project file, so you can wrangle the Apple port.

Dec 26, 2020, 3:49 PM

Here is the source project, which you should be able to export to iOS:

... sends file Nothing.zip

Pippin

Dec 26, 2020, 10:15 PM

Hugely appreciate the thoroughness of all this Andrew - you get it! I had similar experiences with a couple of other engines, where I couldn’t export the nothing until I’d changed it, even if I then reverted it back to the original nothingness. An unnatural occupation.

Andrew

Dec 27, 2020, 9:28 AM

Exactly, it doesn’t pass the smell test. As a matter of principle, I want to be able to launch the editor, click “New”, and then immediately save the output.

UE4 has a hundred tiny little flaws like this, but it’s still my favorite engine to work with, so far.

And, if I’m feeling saucy, I’m diving down to C++ and doing whatever I want.

But, yeah, UE was historically used by small to big studios that knew what they were doing re: this specific style of pipeline.

Pippin

Dec 27, 2020, 1:24 PM

Interesting to hear about UE4 love. I haven’t tried it out myself, ended up using Unity because that’s what someone was around to show me the ropes on. C++ sauciness sounds fun!

Really appreciate your collaboration on this one Andrew - I’ll of course include our co-authorship on it in the game page and my CV and so on!

So that’s the saga of Andrew being a real champ and going through the process of producing nothing in Unreal Engine 4. You can see he was really careful about it, which I hugely appreciate - have to confess I felt nervous about handing the reins to someone else for fear that they wouldn’t quite take it as deadly seriously as I am in terms of not adding anything to the process if it’s avoidable, but Andrew totally got it.

The resulting nothing experience is pretty detailed because unlike Unity, Unreal Engine 4’s blank project includes an actual platform with a default texture and a moveable camera that you can fly around with! It’s interesting, though, that it does still feel within the realms of nothing anyway? Even though there’s solid ground, a sky, and movement, it’s so clearly placeholder that it ends up being hard to take seriously as a “world”… it’s still not really there, especially with the lack of physics? It’s more of a nothing than the default sokobanning in PuzzleScript for example.

The export to WEBGL in Unreal Engine 4, which is handled, I believe, via a community project, also adds a bunch of extra interface stuff when you run it. You see a status message about it downloading the data for the game (31MB!) and there are a bunch of buttons along the bottom: Pause, Resume, Toggle Log, Clear IndexedDB, and FullScreen. They feel like they’re partly there for a developer to test things and partly for a standard player. I do not know what IndexedDB is. There’s also a message right under the play window saying “Running with IndexedDB access disabled” so it’s clearly a thing alright, but do I have the energy to find out more?!

As I play with the scene a little more I see that it does have physics in that you cannot fly through the platform! You can fly frictionlessly anywhere, but the platform is actually solid. So it feels quite a lot less like nothing and no-world than I’d thought initially.

Return of the guy who’s making this thing (Friday, 9 April 2021, 15:41PM)

Oh yeah, it’s three months later. The semester will do that to you. I’m checking back in with this project as I want to wrap it up over next week ideally.

I re-read the journal above and was entertained and more or less still interested in the things I once said. Really in terms of wrapping this the key things are

- Decide how much text should accompany each nothing on the main page (like, do I want a little paragraph with notes about it? a page of notes?)

- Write the public-facing texts based on the journal entries

- That’s it?

Really there’s not a huge amount to be done with this thing. It feels like it has significant intellectual interest for me personally, but probably not much more than that. I think there’s the public-facing bit to try to at least make an honest attempt to have it be intelligible as to why I think it’s interesting. And then there’s probably the Gamasutra piece / Closing Statement in which I can address some of the broader thematic areas that I’ve found interesting throughout.

Planning a closing statement (13-04-2021 10:57)

I’ve now written capsules for every nothing which allowed me to recapture some of the detail and depth of thought (such as it is) for this project. It remains to try to write some kind of overview that reaches for a more thematic analysis of what happened here and thus to try to clarify its value as a research-creation project.

I think that’s the best approach - identify themes of interest and then use the different games as concrete examples. This isn’t one of those cases where I have detailed “design decisions” because I didn’t particularly have to make any of those, it’s rather examples of what the engines themselves did in response to the project. Maybe a little bit of “player experience” in there too.

So what are these themes then, Pippin?

- Nothing is nothing is the overarching theme of course - the premise of the project is that you can learn about the engines and they’re understanding of what a game is and how you make one based solely on doing nothing with them beyond creating and exporting the minimal project they can manage.

- Code forensics is part of this for me, it’s not something I think about, but this project certainly made me notice just size (thrown into relief by the idea of nothing) and sometimes the source itself (I was curious about what it takes to create nothing)

- So much potential. The majority of the engines accompany the lack of actual content with a large amount of code the majority of which won’t execute. The WebGL build of Unity was interesting for being so small. But many of them contain messes of JS for example that has no data to chew. Computation uncomputed.

- A view to a nothing. The visual aesthetics of the different nothings is of course revealing - you do see something. The Unity view is of course my favourite.

- Templates were surprisingly rare. Bitsy, PuzzleScript and to a lesser extent Unreal each had actual interactive experiences as a part of their default project. When they are present they speak to a kind of cultural nature of the software (Bitsy is charming, PuzzleScript is utilitarian, Unreal is stupid)

- Agency is related to the templates, for sure, but extends beyond that. Some of the game allow the player to actually interact to some extent - clearly the previous three, but also Inform 7 is an interesting case. The blank page/PDF is a very specific example of this. In a sense agency and the templates can be folded into each other as they’re kind of about the same thing? Ren’Py as a kind of UI agency.

- Brand Management. Some of the engines advertise themselves by default (Inky, PuzzleScript, Flickgame, Construct 3, Unity, Unreal). Presumably in all cases we can read this as a kindly invitation to the player to step through the mirror and become the creator. It feels more predatory or vain in the cases of the larger companies, however. It’s also quite a meta idea that the game world would include a reference to its inner workings.

- White Box. Twine is the one engine that explicitly references its own nature as a tool for use. This could be folded into Brand Management in a way, if I reframe it more as the visibility of the tool. “Your tool’s showing.” It’s not really a white box obviously, more just visibility of the structure of the tool itself in Twine rather than just the name of the software and a possible link.

- Nothing’s easy. Something about some of the technical details around actually producing nothing. Deleting the “e” in Inky. Downloading the export template in Godot? .gblorb in Inform 7 a barrier to play.

Okay well there’s stuff there obviously. There’s stuff there. I’m feeling a slight loss of steam so I might head over to the press kit and make that part of things quickly now while I have the energy. I think it’s probably a matter of folding this down to about 5 themes or so, illustrated with specific examples, and which all help to tell the story of “nothing is nothing” which is the presumed title of the piece?

OKAY SOUNDS GOOD PIPS.

Planning the closing statement (14-04-2021 10:27)

Nothing is nothing

- Introduce the project and method

- Point out the most obvious outcome that nothing is nothing and introduce thematic areas

- Process - illustrative issues like the “e” in Inky, .gblorb in Inform 7? (This feels a tiny bit weak to me, not enough juice to mention?)

- Code - size, potential computation, layers (PuzzleScript on JavaScript)

- View - Unity’s horizon, blank squares, Ren’Py UI??

- Action - nothings that can be played (Bitsy, PuzzleScript, Unreal Engine, Inform 7, Ren’Py)

- Meta - engines that self-reference as advertising/invitation or Twine special case

- Conclude with positive outcome of looking at nothing, reiterate nothing is nothing

Screenshots throughout, links to the actual playable games.

p5.js Web Editor (20-04-2021)

I’ve start adding a few new nothings to the suite on recommendations from people on Twitter who have viewed the project. Yann Seznec suggested using the p5.js Web Editor which is quite genius! I’m very attached to p5.js in general because of my teaching of course, and it’s also really really interesting to present the project as its code foremost, with the additional ability to run the program. The code it always visible and the user could edit that code to explicitly build upon the nothing. This keeps the nothing much more explicitly alive than the others I think, which I really like - it’s in some ways the ultimate extension of those nothings that link to their editor’s homepage etc.

I’m also not sure how to write about the additions because it’s weird to add a journal entry like this as well as the documentation in the main README pointing to the game… they’re kind of the same thing, there’s no separation of thought process or waiting time to simmer ideas. Nonetheless, here we are.

ZZT (20-04-2021 15:03)

I started writing the main text about this and then kind of floundered so I’m going to write my thoughts here in a less-giving-a-shit way. So, ZZT is a DOS program from 1991 that lets you create genuinely quite remarkable worlds out of ASCII (and ANSI? It looks like ANSI as I remember it but I don’t know if that’s technically correct or what being technically correct would mean?). Making nothing in ZZT proved to be somewhat harder than I wanted because

- BOO! I started with Boxer but the ARM version for the M1 AirBook I’m using did run

- YAY! Then I used the old Boxer and that did work and let me run ZZT obtained from the DOS Games Archive

- BOO! Then I spent an embarrassing amount of time unable to make anything work in ZZT because I didn’t understand there was a modal dialog at the start I could only get rid of with ESC or Enter (I even looked up “keystrokes not working in ZZT” and stuff, oh god)

- YAY! Then I got really excited because making nothing in ZZT is quite appealing and leads to an avatar face in a big empty room with walls

- BOO! But then I could find the fucking .ZZT file that represents the game, it kept disappearing every time like it had no permanence

- YAY! Then I figured that if I ran ZZT directly in DOS BOX I had clearer access to the file system because I could just mount the ZZT folder in DOS BOX (whereas I had no clue where Boxer was hiding stuff)

- BOO! But then a .zzt file isn’t very fun for anyone and I was thinking I’d probably have to include instructions for how to download ZZT and run it in DOS BOX and blah blah blah which is a downer for everyone?

- YAY! But then I found Zeta which can run ZZT in the browser and it JUST WORKS (after a bit of fiddling)

So the upshot is that I do have a distributable NOTHING.ZZT that can be played in the browser and features a happy face in a big room that can move around and doesn’t have any ammo or torches (these are things mentioned in the standard ZZT UI).

The NOTHING.ZZT file representing that game is 1KB in size. It’s really little if you look at it in a text editor. I can’t paste it here accurately as it looks like a bunch of special characters massively fuck it up for display.

The other really interesting thing about ZZT as a platform for Nothing is that by default when you play a ZZT game you’re also running the software that can create a ZZT game… the editor and player are the same thing and not hidden from one another at all. It’s a bit like the p5.js Web Editor in that way, but more user friendly and aimed at non-coders. So again you’ve got this idea of a bridge from game player to game maker that I think is really neat and especially, especially strong in this instance.

batari Basic (21-04-2021 13:35)

batari Basic is a programming language for the Atari 2600 that compiles to binaries that can be read as cartridges in emulators for the system. I assume one could also produce an actual physical cartridge from its output too.

The process for this one was to create a completely empty batari Basic file called Nothing.bas (using cat in the terminal seemed like the fastest way). That’s already of interest to me since it’s not a system that has some specific workflow for creating a new project - rather you need to just “write a dang program” to make it work. In that situation, it seemed more appropriately nothing and low-effort to create an empty file and then compile it.

The batari Basic compiler didn’t object to compiling an empty file to a binary, which is nice. The binary produced is no longer of size 0, it’s a file called Nothing.bin that is around 4KB according to my computer. The fact it has some size lends it a certain kind of legitimacy as presumably there’s boilerplate stuff in there that renders the file recognizable as Atari 2600 data specifically rather than just, again, an empty file.

In getting the file to play nice with Atari emulators like Javatari (web-based) and Stella (for desktop), I ended up renaming the file to Nothing.a26 as that extension helps emulators officially recognize it as being for the Atari 2600. Javatari wouldn’t even let me choose the .bin version as a cartridge to load.

In Stella, loading the cartridge yields what you might expect: a blank black screen. This is true for Javatari too except that it briefly displays an error:

This makes me question whether the cartridge file is actual being loaded at all or actually just breaking the emulator. It’s not clear to me what should happen, and I don’t quite have the patience to learn enough about the systems and emulators to get to grips with what’s “truly” going on there. It doesn’t generate an error in Stella, so I’m going to assume the cartridge “runs” in some sense and produces the nothing we see - certainly no visible error message on the part of the emulated Atari 2600 at least (if it ever has them), nor any kind of graphics error you might imagine seeing as a representation of that error.

The Javatari emulator is really fun because it bothers to represent the surrounding idea of a game system, and I particularly love the touch of the little cartridge labelled “Nothing” that’s visible at the bottom there.

This is probably a bit of a personally significant nothing too, because I’ve based various ideas off the aesthetics and system limitations of the Atari in the past (Jostle Bastard, Jostle Parent, Lo-Fi Dick Fight, Combat at the Movies). To actually “work” with an underlying compiler, even if it’s to compile literally blank code, is quite pleasing to my mind.

GB Studio (22-04-2021 10:32)

GB Studio is a tool for creating Game Boy games, including exporting to the Game Boy ROM format, so presumably legitimate in terms of compiling down to something that an actual Game Boy understands code-wise. Also exports to web, which is nice!

It’s very “easy to use” in the nothings sense because you just fire it up and it defaults to creating a new project and off you go with your exporting.

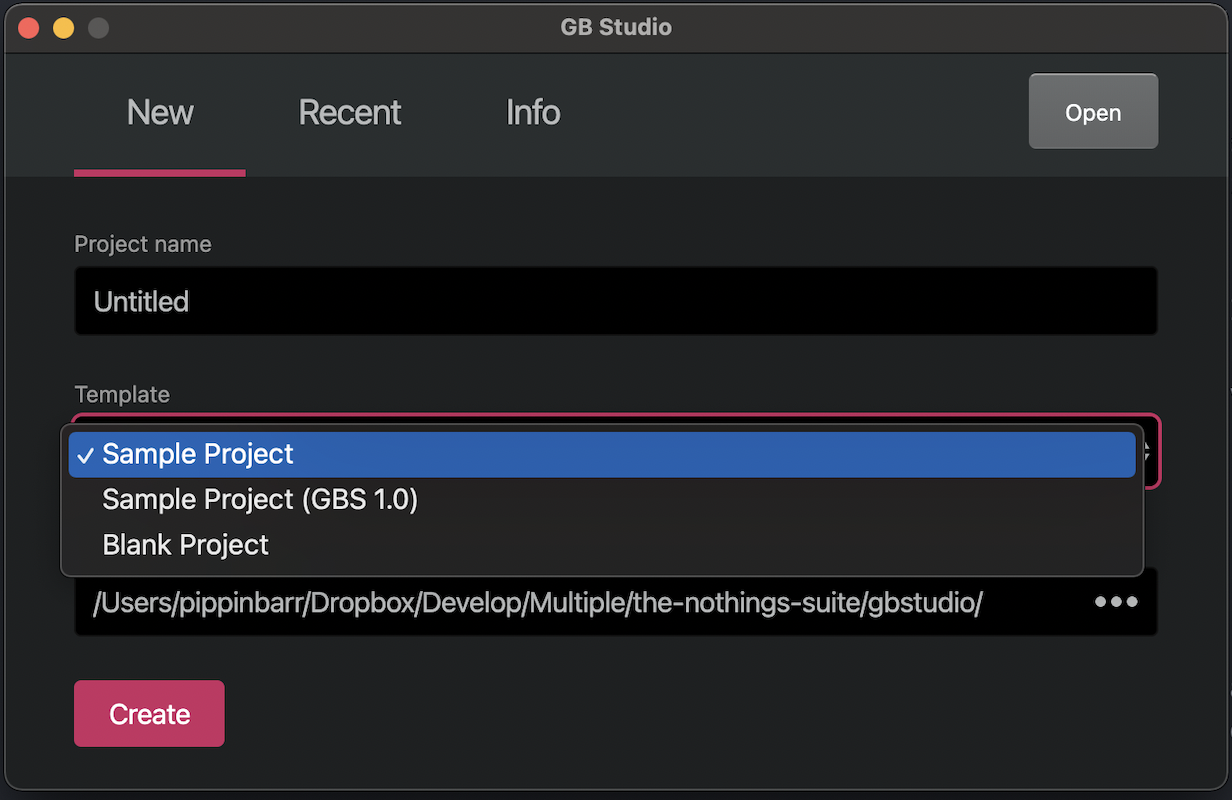

It does create a familiar tension in the overall methodology of this suite, though, which is that when creating a new project the default template to use is the “Sample Project”, but within the dropdown menu for templates is also the “Blank Project”:

This immediately generates a tension between the two most obvious understandings of The Nothings Suite, that is is either a) games with the least possible content, games that are literally nothing or at least an engine’s interpretation of nothing; or b) games made with the least possible effort, games for which I “did nothing” and represent that path of least resistance through the engine. a would indicate the “Blank Project” is the right way to go. b would indicate the “Sample Project” is the way to go as it’s the default.

Further complicating this is that the Sample Project is, understandably, quite fully featured and thus shows a ton about the engine that would thus make it quite a nice nothing for a player to see and think about…

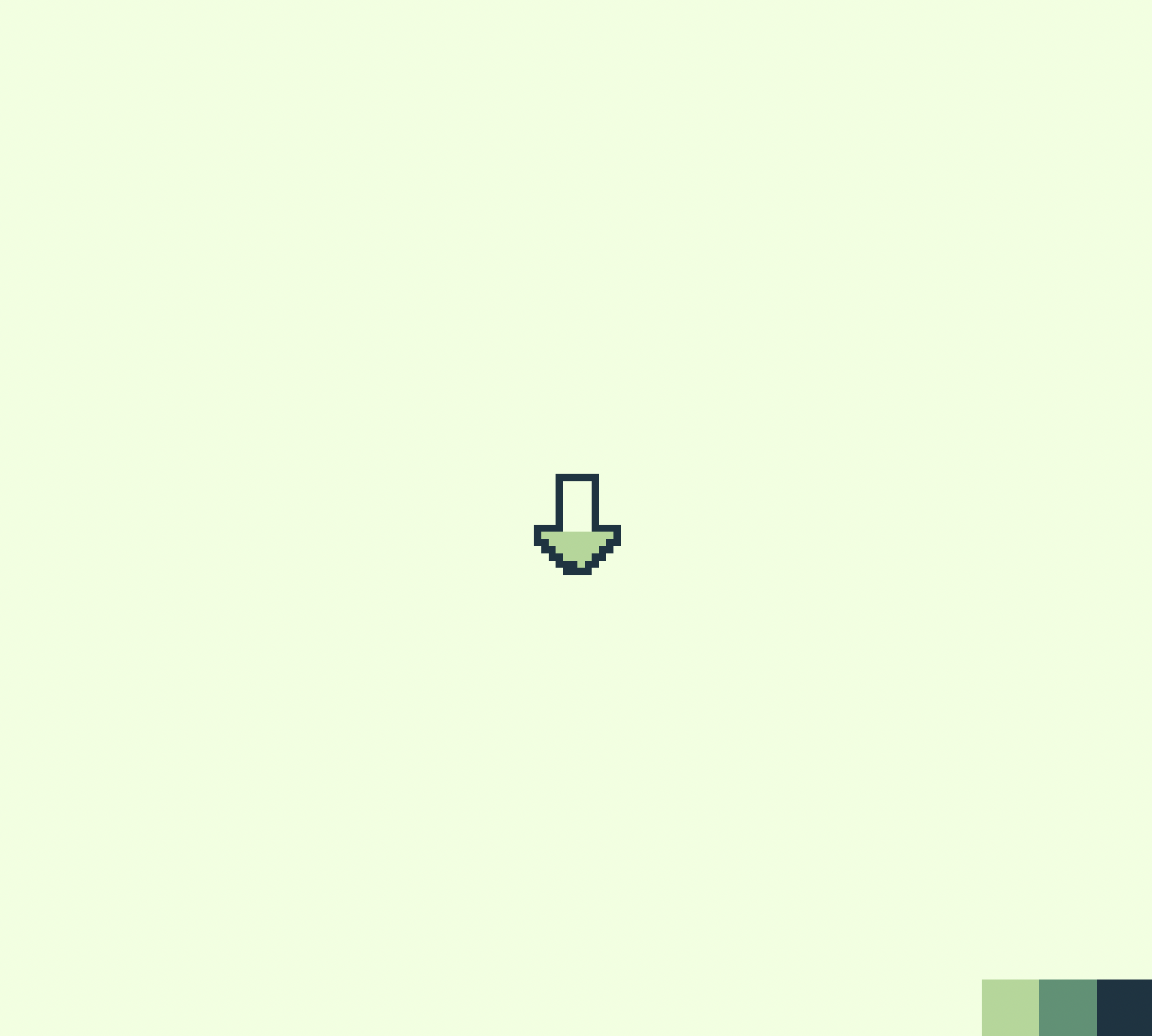

But, the Blank Project is actually quite a beautiful little distillation of nothingness too, featuring a moveable arrow on a screen plus a little color palette…

As such, either of these two ideas seem like they yield a worthwhile nothing to show the world, which pushes me back to the core existential question about the nature of the suite again, damnit.

Have I already solved this problem and I should not worry? At the top of the release of the games it says

The Nothings Suite is a collection of (extremely) short videogames made with diverse videogame engines such as Unity, Twine, and PICO-8. In each case, a game has been produced with the engine using, as much as possible, no creative input at all. That is, in the ideal scenario I open the game engine, save the project it creates by default as “Nothing” and export it for play. This means you get to see each game engine’s idea of what “nothing” (or at least no effort) looks like when you set out to make a game with it.

Which mostly suggests I’m aligning to the idea of providing the least input. Except that in referring to a game engine’s “idea of nothing” I’m talking more about the potential for including blank projects explicitly. Le sigh. Is it the case that I should be using a blank template if it’s available, even if that requires me to explicitly find that template in a menu (SO MUCH WORK RIGHT?!?!?!?!).

Now I’m convincing myself that the Blank Project is the way to go. But would I be able to say the same if the blank project was truly blank? Wait it IS truly blank! Right, that’s the other thing, because the process with the Blank Project is like this:

- Select Blank Project template

- Try to export

- Read error message saying you can’t export a project without a scene

- Add a scene

- Try to export

- Ta da

That is, in choosing the Blank Project you end up being required to do more work (and less nothing) in terms of explicitly adding a scene because otherwise it literally won’t release. I’m comparing that a bit to the Godot Engine’s nothing, which similarly begins with no scene but doesn’t require a scene to compile and release, and therefore ends up throwing an error in the console. Should I have added an empty scene in Godot? No, right, because the idea is what the most nothing the engine will “tolerate” to some sense? But no, because in that context for GB Studio I would go ahead and delete everything in the Blank Project scene before proceeding right? But I don’t want to do that because that just leads to the “everything is a blank rectangle” path?

I mean, there’s probably a core truth to this overall project that it’s very subjective at a certain point what I’m counting as nothing, but I want it to at least feel a bit rigorous? That I should have rules for how to proceed? So is it

- Open the engine

- (If needed) create a new project in the blankest way available

- (If needed) add minimal elements until the project is exportable

- Export the project

Step 2 tells me to use the Blank Project in GB Studio rather than the Sample Project. Step 3 tells me to add a blank scene to the Blank Project prior to exporting.

Do these encoded rules change anything about any previous engine? Let me take a scan through the list. I mean, Inky was interesting because it needed step 3 (the insertion and deletion of a character to be allowed to export). PICO-8 used step 3 in requiring an image to represent the program. Ren’Py uses step 3 in order to choose resolution and palette…

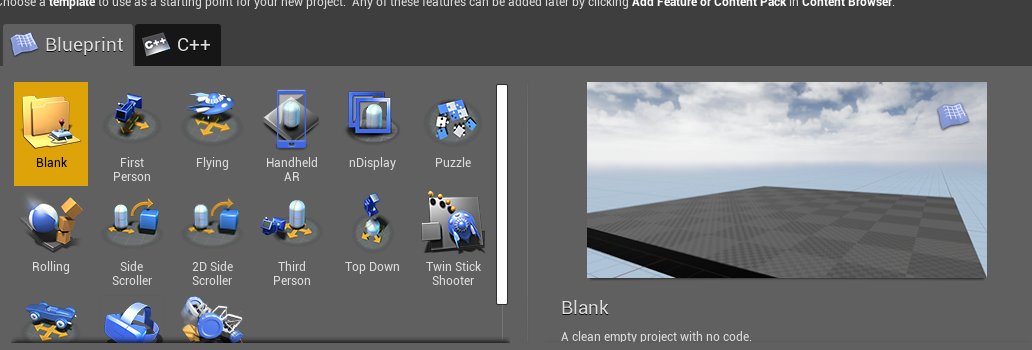

So no, these rules seem to represent a reasonable understanding. Really I’m mostly explicitly adding rule 2 to the process which is telling me to select Blank Project and not Sample Project in GB Studio specifically. This may also refer back to Unreal Engine 4, in which Andrew also used a Blank Project, though it looks like it highlights as the default option according to his screenshot.

So there you go, we’re doing okay here methodologically and I think we now know we need the GB Studio nothing to be the Blank Project and not the Sample Project. Thank god for cold hard logic and not at all any emotional decision making ever in my games.

Adventure Game Studio (23-04-2021 10:43)

Started in on AGS this morning after we had finished up our morning game playing. Downloaded the current version (3.5). Fired it up. When starting a new project there is a “Blank” template to select (though it explicitly advises you against this which is kind of interesting, I’ll need to get some screenshots).

But the Blank template isn’t compilable immediately because you need a room. So I stared at the UI until I worked out how to add a room (blank of course). But then it still wouldn’t compile because somewhere it’s set that the starting room is “-1” and that’s not a valid room and so, no. But as yet, just in flailing around in the UI (which is not simple) I cannot find where the room is set to -1 and I’m wondering if it’s a default that’s not explicitly set anywhere but it rather something I need to explicitly encode myself somewhere in the code or one of the many lists of properties.

Which is to say that this is an interesting one processually because of how hard it is to release the blank template. Is this then a case for switching (as advised by the tool itself) to a more complex default template? Or do I fight onwards to find my way to blankness? Maybe I can look at the template, find out where the fuck it specifies the starting room and then reverse engineer that into the blank template? Quite a struggle. The struggle is real.

So anyway, back later with the results of this, just wanted to update you.

Adventure Game Studio continued (23-04-2021 14:45)

Finally got a blank game working after consulting this discussion from 2011 that points out that your character needs to have a starting room defined, which the blank project character does not because there are no rooms defined when the software starts. It kind of begs the question why it doesn’t just start with a room so it’s buildable from the beginning, but there you go.

I think there’s something at least a bit interesting about having to work at getting an empty game to compile in this manner - it’s definitely the most confused I’ve been and the most research I’ve had to do to produce nothing.

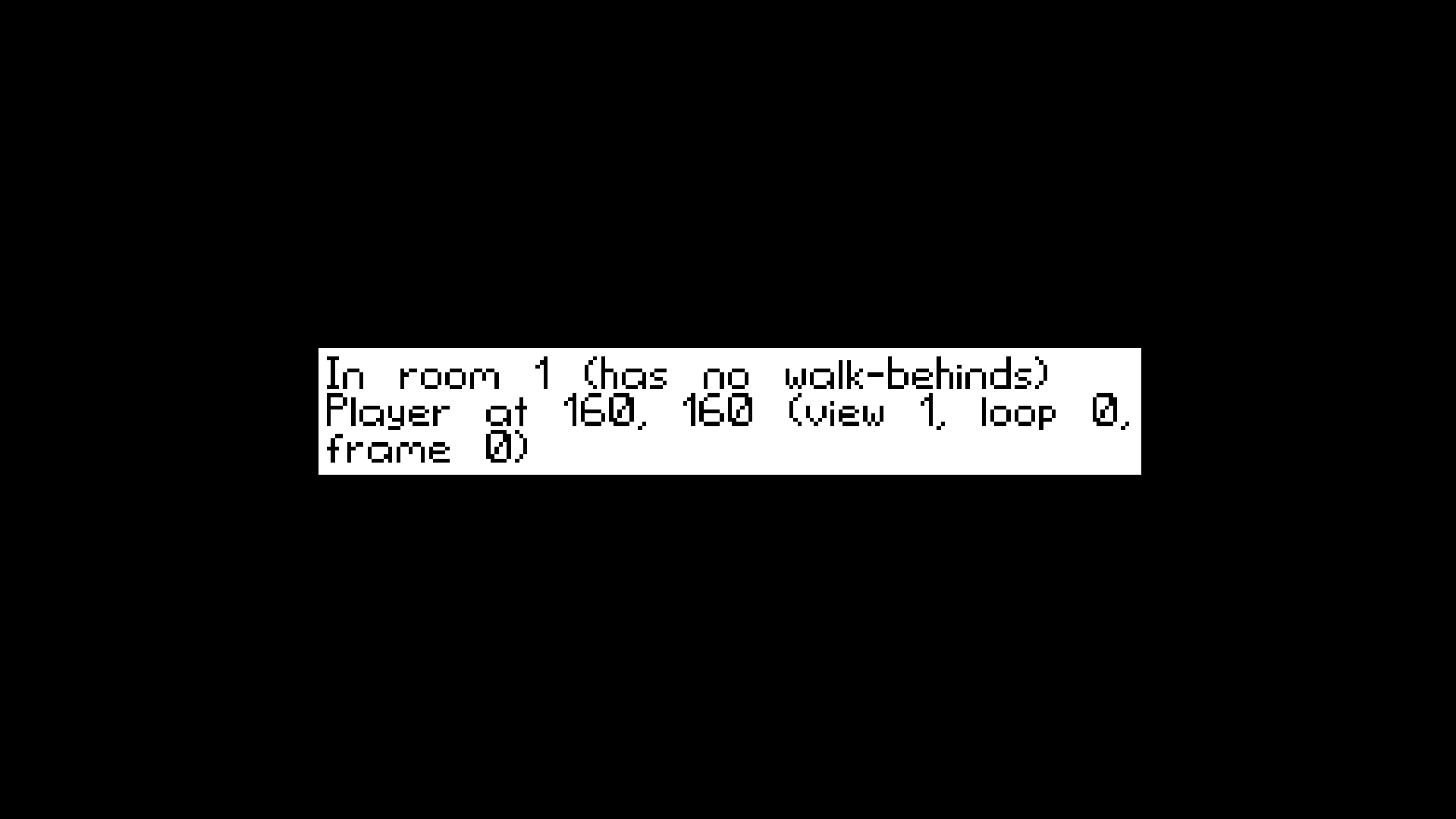

The build itself is an .exe, so Windows only which is something in itself and obviously connects to the nature of the tool and its community. The other thing about the build, which just displays a black screen in fullscreen, is that it has a few commands built in, the majority of which are debug commands! So I guess there’s some debug flag on by default when you start the project.

Ctrl-Q will quit…

Ctrl-D presents information on walk-behinds, player location, characters present in the room (complete with stats)…

Ctrl-X takes you to a menu that lets you select which room to go to (there is only room 1 in this build)

Ctrl-V gives you version information, resolution, graphics library, sprite cache information

There’s something about the fact that these debug menus talk about a room, walk-behinds, a player with a specific location, the possibilities of multiple characters and multiple rooms, that makes it feel like I’m not looking at just a blank black expanse but actually a darkened room. That there’s someone in there and I just can’t see them because the light it off. Without the debug information I think that sense of presence wouldn’t really be generated, even though I know in some sense there “is” a character in the room because I saw that option existed in the tool that created the build.

Meanwhile, just figuring out how to release this nothing has been a pain in the ass. It’s an .exe, so a binary rather than a webpage, and a fully fledged application rather than a ROM file or similar. I tried to put it in as a “release” on GitHub, but this assumes it’s a build of the overall repository which of course it isn’t, it’s just a binary from one of the many parts of the repo. In the end I’ve settled on a .zip of the application inside the source for the AGS project, which is non-ideal and breaking the structure the tool came up with, but at least allows me to allow people to download it successfully I think.

PuzzleScript addendum (23-04-2021 15:38)

@zarawsome let me know that PuzzleScript actually does have a Blank Project option hidden inside one of its menus. Under “advanced” which is both funny and of course appropriate because it would require the most work (and actually more than one engine kind of warns off using blank templates in case you’re new and might get confused).

This did lead to some anguish because going with my new rules would suggest having to shift the PuzzleScript Nothing to this Blank Project. BUT! Fortunately(?) it doesn’t actually run as is, because it doesn’t think there’s a “cartridge” loaded by default and has the following error:

No collision layers defined. All objects need to be in collision layers.

It’s true that I could find out how to define a collision layer and so forth, and that might be in the spirit of things (certainly in the spirit of the AGS saga above), but I think I’m mostly comfortable with leaving it alone? Or am I? Shit…

I mean, just for interest’s sake I followed the error messages along through comparisons with a non-empty project. There is something interesting about the gradual construction of a viable project by responding to the messages about non-viability from the engine to be honest. EVEN THOUGH the result is just a disappointing single coloured screen, there’s probably something kind of strong about the processual element if I document the “conversation” that exists between me and the system to find out what’s good enough to count as nothing?

Or … I don’t know, I’ll sleep on that.

LÖVE (26-04-2021 11:20)

Context

Cody put together a nothing in LÖVE which led me to want to make one too in the interests of comparison. If two people make nothing with the same tools, are those nothings identical or not? What could the differences be? Metadata? Understandings of the underlying system? Release platforms? Etc. Cody has authorship on this one, so I’ve checked in with them on whether they’re happy for me to have made one too and to link between them, but in the meantime I’m going through the process anyway as I think it’s intriguing even if I don’t officially “release” this one. I’m purposefully not looking at cody’s nothing until I’ve finished my own for fear of influence, though I already know their Windows release is 3MB which might be meaningful (though I doubt it for reasons). Well, that and the fact that their Linux release is only 188 bytes which is… very interesting indeed and suggests radically different approaches to compilation/release on the two systems. Hmm. Anyway, can get to that later as I’ll recreate my own releases which will almost certainly have similar properties.

So, how does the process go?

Well, LÖVE is a free 2D game engine that lets you write games in Lua. I’ve never made anything in it but I’ve been impressed on multiple occasions by work I’ve seen Cody do in it, more their earlier experimental stuff than the more game-like stuff. I remember a brain surgery textual game I think, and it has stayed with me in a strong and ambiguous sense impression. Anyway.

My main “functional” relationship to LÖVE has been accidentally hitting a key combination in Atom that launches the LÖVE loader which tells me I don’t have a LÖVE program or something.

Building the .love package

As such, we can consider me a complete beginner with LÖVE and therefore without any obvious preconceptions about how to make nothing with it. As such, I’ve relied on the tutorials. I have, as I write this, produced some a nothing in the sense of a .love file with nothing in it, but I still need to produce releasable versions of this - and all this speaks to the LÖVE process as well. So what has been happening?

Well, first of all I downloaded LÖVE itself for my mac.

Then I went to the Getting Started page on the website to learn how you make a LÖVE game. Importantly, though, given that I’m starting this project from scratch and therefore have some amount of discretion, I did create the main.lua file, but I left it blank rather than putting in the suggested “Hello, World!” code. At that moment it remained to be seen whether the LÖVE compiler/runtime engine would accept blank code as a legitimate LÖVE program. (Actually this is all making me wonder about larger philosophies in software engineering and programming language design around the legitimacy or not of a blank program.)

To check this, I ran the nothing project with the LÖVE application and it ran fine, presenting the pretty boring black rectangle in a window kind of a nothing that’s rather familiar. So the minimal LÖVE is a blank main script. As far as I can tell you can’t get it to run without the main.lua file being in place, so that’s the minimum in terms of my understanding, an empty Lua file.

Building for Mac

To actually distribute a LÖVE game I’ve been following the instructions on the Game Distribution. Notably you create a .love file by zipping up the game files in your project folder (in my case just the empty main.lua) and renaming the resulting archive with a .love extension. Doing that yields a nothing.love which is 196 bytes according to my Mac, presumably all or mostly all ZIP headers etc.

To actually release the game, you then need to package the .love file along with the LÖVE engine itself as far as I can tell. So for a Mac release I need to essentially copy the LÖVE application on my Mac, rename it to Nothing.app and store the .love file inside the .app package in a specific location as well as make some other edits to have it behave correctly. Let me try this…

… and indeed after following those instructions (which include changing names and bundle IDs in Info.plist as well as removing a section) I can run the game locally. However, this version presumably doesn’t live up to Mac’s security standards. It’ll either be totally unrunnable on another computer, or it’ll be one of those apps you have to open via the context menu to tell the computer to go ahead and run it. If it’s the former, then this doesn’t count as an actual release, if it’s the latter then I’m satisfied… so now I need to send it over to my other laptop and see how it responds…

… and it’s the former, so this is not really a release at this point since it cannot be run on another system. This actually brings up another issue in the rules since I suppose I haven’t actually specified that a nothing needs to be runnable, but it’s kind of implied with the idea that it needs to be considered by the engine as a runnable/working game. I guess now we’re asking a new question which is whether the operating system thinks so too, and that’s open to interpretation in terms of whether I think it counts. But if another player on another mac can’t run it, then it’s not really a proper nothing game, it’s just a broken piece of software, so I guess I have to pursue this further!

… tried the extra step of compressing the app first, but it’s still not passing muster with my computer. Heaving sigh.

… carrying on with this I have now read a dizzying amount of information about creating certificates signed and unsigned. For right now it seems like an unsigned certificate is the way to get to that moment where your application can be opened in something like Mac OS (after they do the “trust this untrustworthy thing” step) and I think that’s as far as I want to go right now, though this has interested me more generally in this whole idea of the trustworthiness of nothing. So I think I’ll self sign it, but also investigate more deeply ideas around more secure signing via Apple since I do have a developer account anyway…

… and hey presto that does work to create an unsigned, insecure nothing application for Mac OS. it is 15MB Because that’s how large the love.app file is in the first place plus the few extra bytes my “code” represents.

Building for Windows

So with that in place let me attempt to create my Windows build…

Windows worked out fine with the instructions inasmuch as I have an archive for it. I need to test it on the PC Bong to find out if it works though I suppose. Let me do that now…

… indeed it works.

So there we go, I have two releases. But one more interesting thing!

The substance of nothing

Cody’s Linux release is just the file nothing.love but his file is 188 bytes and my file is 196 bytes. Where are those 8 bytes coming from? I’m somewhat assuming it’s a difference between the ZIP utilities on our respective systems? Maybe a versioning thing? I’m assuming that Cody has a blank main.lua just as I do, but in creating our different packages there’s 8 bytes floating around.

So yeah, essentially I think we both started with a blank file called main.lua. Then we both zipped it and renamed the resulting archive to nothing.love. In that process the only place that can be causing a difference is the compression. And indeed I note that if I compress main.lua from the GUI in Mac OS I get a 496 byte file as a result, compared to the 196 bytes I’m getting when I zip from the terminal. Interestingly further, when I zip the file with slightly different notation I get a different size…

zip nothing.love main.lua is 166 bytes

Even weirder, I now cannot find the command I entered to get the 188 byte version of the file?

Also notable: this feels competitive in an interestingly stupid way? Like, there’s some weight to having the smallest possible nothing, shaving bytes off while maintaining a runnable program? At least I have an instict to prefer it and to be interested in the difference.

PuzzleScript v.2 (27-04-2021 15:33)

Well, having thought about @zarawesome’s note that there’s a blank project in PuzzleScript I’m going to document the process of turning that into a viable Nothing. This will be an additive process of trying to convince PuzzleScript to accept the code as a game. It’s a bit like AGS earlier on in terms of figuring out the minimal changes to a blank project to make it compilable, but I think a little bit more involved, a few more error messages.

I quite like this idea of “nothing by accretion” because it makes essentially no sense at all.

Let us begin.

We start with the blank project template under the “Advanced” section. When we run it we see:

No collision layers defined. All objects need to be in collision layers.

Now obviously this isn’t telling me how to solve this problem, but I can see a COLLISIONLAYERS section in the comments of the code, so I need to put something in there. I’ll have to refer to a non-blank project to understand what that is, so I’m going to have the non-blank standard project open at the same time to refer to how it deals with these different (apparently mandatory) categories…

In the non-blank game there are three lines listed in COLLISIONLAYERS, which are Background, Target, and Player,Wall,Crate. I don’t understand what that means particularly, but I’ll throw the first one into my project and see how it response.

So, I add Background to my COLLISIONLAYERS section and…

line 16 : Cannot add "BACKGROUND" to a collision layer; it has not been declared.

You need to have some objects defined

Fair. The Background doesn’t exist. I need to have some objects defined. I see there is an OBJECTS section, and that in the non-black project there is code defining this Background thing and its color (GREEN), so I’ll do the same…

So, I add

Background

BLACK

to the OBJECTS section and…

error, didn't find any object called player, either in the objects section, or the legends section. there must be a player!

No levels found. Add some levels!

So apparently the Player object is the most important thing and the game cannot live without it. Also I have no levels, which… yes that’s true.

Let’s exchange our Background for a Player by adding

Player

GREEN

to the OBJECTS section. And swapping Player into the COLLISIONLAYERS Now we get…

you have to define something to be the background

No levels found. Add some levels!

Okay well I guess we need a background, so let’s reinstate that in OBJECTS and COLLISIONLAYERS…

No levels found. Add some levels!

Great! So it seems like we have out minimal set of things in the world. A Player and a Background, both of which have to have a color and a presence in the collision layers. Now we have to add a level. Looking at the non-blank template, I see that a level is a little ASCII drawing with symbols representing bits of the level. This draws my attention to the fact that there is a LEGEND section that seems to associate symbols with objects, so I’ll first add a LEGEND entry for the player. Of course that doesn’t solve anything, but now I can use that to define a level with exactly one tile consisting of the player???

Which yields

Successful Compilation, generated 0 instructions.

So that’s good. I really like the 0 instructions in particular.

Weirdly when it runs I don’t see the Player color which is what I would assume, I see the Background color. As if the player just isn’t there…. oh wait. I have the collision layers in the wrong order, hadn’t understood they’re also the graphical layering system. When I move the Player to the bottom fo the layers we do indeed see just a single tile taking up the whole level in the color of the player. e.g. we have a level that “is” the player against a background (which you can’t see because there’s only one tile being displayed).

And that would appear to be the minimum. A player and a background (each with colors and positions in the collision layers) and a level with a single tile in it representing the player (though note the single tile could represent the Background if we wanted, there’s no requirement to have the Player actually in the level you create).

Not a game you can finish, not as sophisticated as the Sokoban from the default, but certainly more nothing-y.